The Atlas of Live Players and Institutions

Each new weekly Brief brings us closer to creating not just the best guide to our changing world, but a product like no other: the first-ever atlas of institutions, industries, and live players.

Every Bismarck Brief is an in-depth investigation of a key institution, industry, or influential individual that guides you through the fundamentals, strategic relevance, and likely futures of the subject at hand. In rigor, scope, and punctuality, there is no other product out there like the Brief. Since launching in 2021, we have issued more than 150 Briefs. At this current methodical pace, we might reach the 1000th Brief sometime around 2040. As I am an advocate of long-term thinking and planning, it is only natural that I explain my long-term vision for the Brief. Before I continue, please note that this letter is long and includes many detailed maps and charts. Rather than in your inbox, you may prefer to read the browser version here.

Bismarck Brief is not just a series of discrete, unrelated reports. It is rather a single coherent research project to map out the global landscape of live players, functional and dysfunctional institutions, new technologies, and fundamental economic and demographic flows. At a thousand Briefs, the total word count of this corpus would be measured in the millions, more like an encyclopedia than a newsletter or book. The end result will be an informational and intelligence product that has never existed before: an up-to-date atlas of institutions capturing the shape and structure of our civilization—and the people piloting it—in unprecedented detail.

Our work so far has already made it possible for our paid subscribers to rapidly acquire an informed generalist’s understanding of numerous key domains, apprised not just of the latest developments, but also the underlying dynamics driving the course of events forward. For the live player who needs to deeply grasp a domain in the shortest amount of time possible, there is no better source of navigation-grade intelligence than the Brief.

Consider energy. From charting which technologies will be viable in the near future to planning for the wide-reaching impacts of climate policies, an understanding of the state of global energy consumption and generation is one of the prerequisites to effective economic strategy, whether as an individual, nonprofit, company, or government. The largest sources of electricity in 2023 were coal, natural gas, hydropower, nuclear, wind, solar, and oil. To understand the state of energy, one would need to understand the physics, technology, and industries behind all these sources of energy.

That is precisely what Bismarck Brief offers right now, and, like an interactive encyclopedia, it can be shown with one short bullet-point list of links to Briefs, that can fit in a short email:

Energy:

Nuclear energy:

Hydrocarbons:

Similar lists could be made already for many other domains, though, since our work is far from complete, most would be composed of institutions and industries yet to be investigated. Consider the supply chain—and demand chain—of advanced semiconductors:

Advanced semiconductors:

Major users:

Investors:

To be Briefed: Sequoia, etc.

To be Briefed: Chinese funds, Brookfield, etc.

Designers:

Licensors:

Manufacturers:

Equipment suppliers:

To be Briefed: Carl Zeiss, nascent Chinese suppliers, etc.

Pick a domain, and in all likelihood the Brief is already a small and growing wealth of knowledge on that domain:

In emerging and speculative technologies, we have investigated fusion, quantum computing, brain-computer interfaces, legged robots, drones, 3D printing, supersonic flight, xenotransplantation, and the cure for obesity.

In the strategies, challenges, and live players behind successful small states, we have investigated Singapore, Monaco, Estonia, Dubai and Abu Dhabi, Israel, and even the Vatican.

In multi-generational dynasties that head powerful institutions, we have investigated the Sulzbergers, the Wallenbergs, the Bechtels, and, in Asia, the families behind Samsung and Hyundai.

In the Latin American countries that compose most of the Western Hemisphere, we have investigated the economies and political economy of Mexico, Brazil, Chile, Venezuela, and Argentina.

Of the world’s most valuable companies, many have been investigated by the Brief already, including Apple, Nvidia, Amazon, Saudi Aramco, Meta, TSMC, Visa, Novo Nordisk, Tencent, and Netflix.

On China, the Brief has investigated so many people, bureaucracies, companies, and aspects of Chinese society that even listing them all at once would be too tedious to read. Suffice it to say that some of my personal underrated favorites from over the years are not just our unsurpassed top-level review of China’s energy strategy or our investigation of China’s rapidly advancing nuclear industry, but also Briefs on neglected aspects of Chinese soft power such as China’s film industry and the growing power of China’s elite universities—every year going to the right school matters more in China and local party connections matter less. Unchecked, such a trend would over time completely transform the party regime.

There is great value in personally reading diverse, contradictory sources to gain an understanding of a subject. But there is no publication besides Bismarck Brief that goes through as much strain and effort to reconcile and connect the vast scope of subjects and viewpoints investigated, and unify such disparate analyses into a single coherent picture of the world. On both the larger and smaller scales, this not only saves our readers valuable time, but enables whole new categories of insight.

The Earth As Seen By Bismarck Brief

Many domains might be more easily explored with a bird’s eye view than an encyclopedic index. I highly recommend you use and bookmark The Geographical Bismarck Brief. Viewing this data through Google Earth—which you can do yourself by clicking the menu with three dots in the top left—allows us to see an actual interactive atlas of institutions and live players develop in real time. For example, the satellite view of North America at the beginning of this letter. And here is what Asia looks like from the perspective of Bismarck Brief so far:

Here is what Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East look like:

At this scale, one cannot quite make out all the institutions and individuals investigated by the Brief, since both tend to cluster closely in particular cities. This is because cities are the command centers of elite classes. Though a war may happen on a far-off frontier, and an explorer may voyage to an undiscovered country, the decision to deploy the army or the explorer is made in the city. The urban halls of power are where those capable of making such decisions meet, deliberate, and organize. Their citizens live together in proximity and organize their daily lives around such networks and opportunities.

The trivial task of walking down a hall and carrying out an informal conversation can save hundreds of man-hours of paperwork. The more physically integrated an organization is, the faster it can communicate with itself, and thus the faster it can respond to circumstances and succeed at whatever task it has set out to accomplish. Voice is a better carrier of information than a memo or email, and in-person communication is superior to a phone call. It’s easy to see why living in the right city, alongside the right people and organizations, is so valuable.

Cities are like massive information-processing units, with real-estate markets revealing the value of being able to access the networks involved. People put a dollar value on physical colocation and proximity to others who have similarly paid a high price to access density. This implicit sorting lies at the heart of many cities. Retaining key locations in a city is often one of the primary goals of prominent organizations. The most central locations are often the surest markers of privilege, authority, and legitimacy.

As a result, if we just zoom in, we can begin to see a literal landscape of institutions. Consider what the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area looks like:

A dense urban core filled with powerful government bureaucracies, ringed by suburban military and intelligence agencies, defense and infrastructure contractors, and increasingly software and even biotechnology companies. If we zoom in further to the core of the capital, we can ultimately make out the very buildings and streets that house and connect such major institutions:

The familiar maps of many of the world’s major cities are recontextualized when we begin plotting the important organizations that make them up:

You can view any area of the world as seen by Bismarck Brief here. If you aren’t already a paid subscriber to Bismarck Brief, I warmly invite you to become one and join us as we create the first-ever atlas of institutions, industries, and live players, with a new in-depth investigation in your inbox every Wednesday at 2pm GMT sharp:

Measuring the Magnitude of Institutional Influence

The long-term project of investigating all of the world’s most strategically relevant institutions is valuable and worthy in and of itself. But it also creates the possibility for new kinds of insights into industries, societies, and civilization as a whole, as compounding case studies result in comparisons and observations that have never been made before, giving rise to useful and illuminating new models and theories in sociology, political science, and economics.

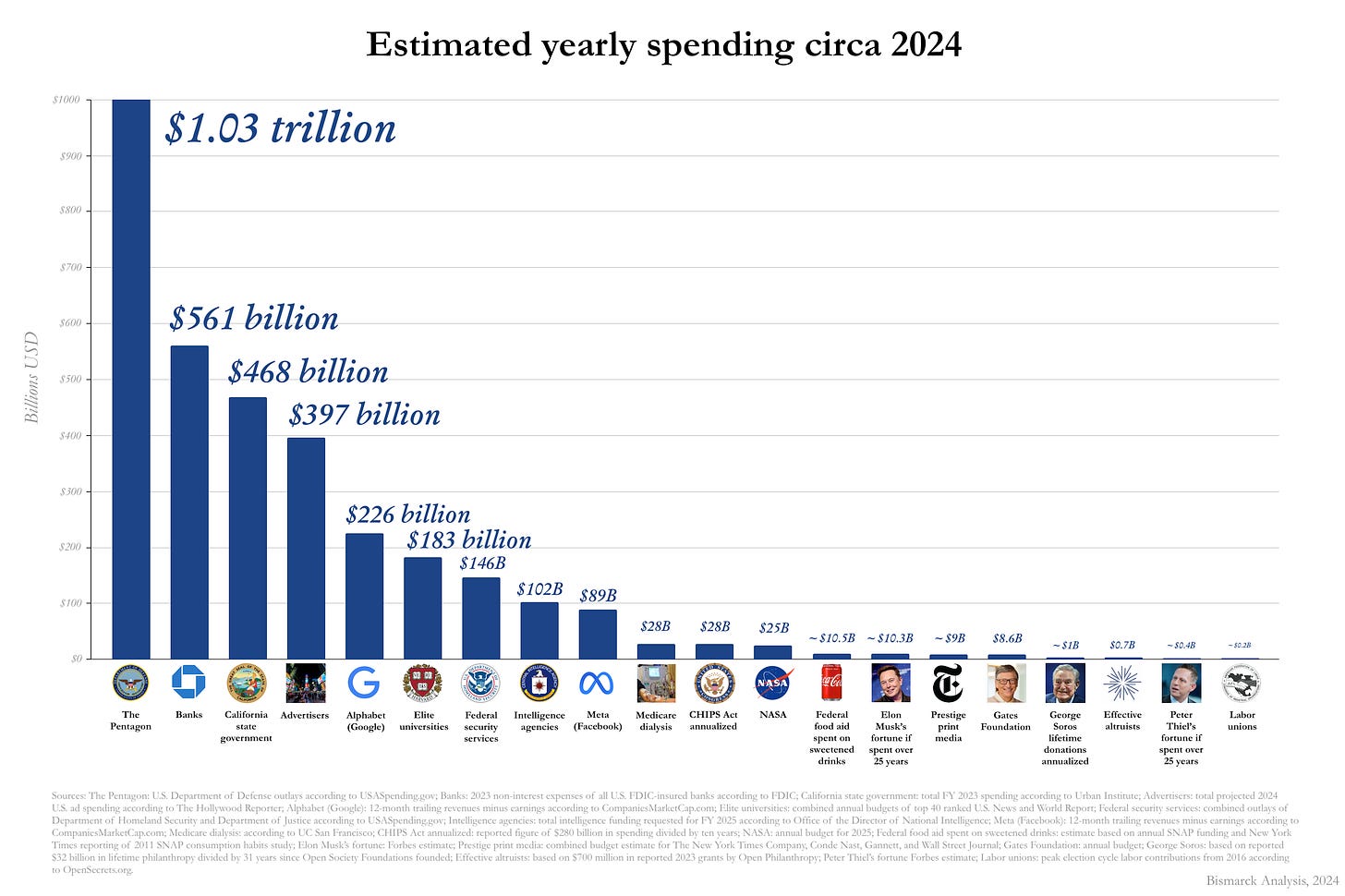

For example, consider the common assumption that the wealthy exert an undue influence on society through spending lots of money. By this same metric, it is not wealthy individuals who are exerting the greatest influence on society, but government bureaucracies, banks, advertisers, and universities:

Spending by wealthy individuals is quite literally just a drop in the bucket in comparison. Even if Elon Musk—the world’s wealthiest person—committed to spending every last cent of his fortune over the next 25 years, he would still spend less per year than the U.S. federal government is estimated to spend on food aid for sweetened drinks and sodas each year.

Elite universities spend a staggering $183 billion per year. The prestige print media—including the New York Times Company, Wall Street Journal, and Condé Nast's publications like Vanity Fair and The New Yorker—spends at least $9 billion per year on its operations. This is more than Bill Gates spends to influence the world through the Gates Foundation and far more than any other individual.

The reason spending by wealthy individuals is put under a microscope is that they comparatively spend too little money. Institutions like bureaucracies, banks, or universities spend enough to be politically indispensable, hiring legions of employees, making or breaking legions of careers, molding the worldviews of legions of educated people, ultimately securing their privileges in law and ritual. In comparison, spending by wealthy people is not just minimal but diffuse, as their particular goals and worldviews diverge widely.

Individual spending is made in large part by the idiosyncratic decision-making process of a single person or small group, allowing it to be uniquely effective or disruptive. Institutional spending is all done by committee and custom. A large part of perceived influence on society is therefore psychologically miscategorized as coming from the quantity of spending, rather than the quality and unconventionality of it.

Wealthy individuals who wish to change society must ensure their spending is not a minor trickle feeding into a roaring river of institutional spending that would exist regardless of the spending decisions of individuals. Rather, it is only through creating new, innovative, and unconventional flows that an individual might succeed at altering the landscape of ideas, organizations, and ultimately outcomes. This capability for experimentation is the unique advantage and key societal function of individual spending, and why individuals can exert any influence at all despite the overwhelming—but static—flows of spending that make up society. Far greater effects could be achieved if more wealthy individuals understood this and liberally used their spending power accordingly.

Another surprising fact about the U.S. economy is that non-profit organizations spend $2.42 trillion every year—this is nearly 10% of U.S. GDP and more than the Pentagon and revenues of all the large software companies combined:

This figure presumably includes many hospitals, universities, and religious organizations, not only think tanks or activist groups. Much of the spending is funded by government grants. But with 35-45% of U.S. GDP spent by the public sector and perhaps up to another 10% spent by nonprofits, it is possible that a majority of U.S. GDP is spent outside of the market, without regard to market signals or forces. It is perhaps time to rethink what we call this economic system.

My goal is to exhaustively investigate the entire global landscape of live players, key institutions, new technologies, and important industries. This does not mean, however, that the Brief must have a definite end-point. The world is not static, and many future Briefs will undoubtedly be updates on institutions and live players investigated before. As a rule of thumb, I aim for a Brief to be immediately relevant for two years after being issued, and due for an update after four years. Though we are still at least a year away from the four-year anniversary of our very first Briefs, I am already looking forward to again investigating the progress of China’s space industry, the ongoing revolution in solar power, Turkey’s innovative drones, and more.

If you aren’t already a paid subscriber, I warmly invite you to become one and join us as we create the first-ever atlas of institutions, industries, and live players, with a new in-depth investigation in your inbox every Wednesday at 2pm GMT sharp:

If you haven’t already, I also warmly invite you to read our recent analyses of how Bismarck Brief outperforms the S&P 500 and how Great Founder Theory informs every Bismarck Brief.

Sincerely,

Samo Burja

Founder and President, Bismarck Analysis