Nvidia’s Successful Bet On Artificial Intelligence

Founder and CEO Jensen Huang had an early belief in using graphics processing units for other computationally intensive tasks. Nvidia’s bet on this idea has been borne out so far.

As of December 2022, the U.S. computer chip designer Nvidia is the most valuable semiconductor company in the world, with a market capitalization of $450 billion.1 Despite a relatively small workforce of just 22,500 employees, Nvidia is more valuable than Taiwan’s TSMC, which has a market cap of $417 billion, and is significantly more valuable than Samsung, Intel, or AMD. The core of Nvidia’s business is designing and selling graphics processing units (GPUs), which are computer chips specially designed to render visuals, especially for the $180 billion global video game industry.2 Headquartered in Santa Clara, California, Nvidia has also rapidly grown in the last decade to become one of the most important companies for the future of artificial intelligence. In 2012, Nvidia’s revenue was just about $4 billion, but reached $27 billion by 2021. As of 2022, Nvidia chips are the most commonly used in AI research papers by a wide margin.3

You can listen to this Brief in full with the audio player below:

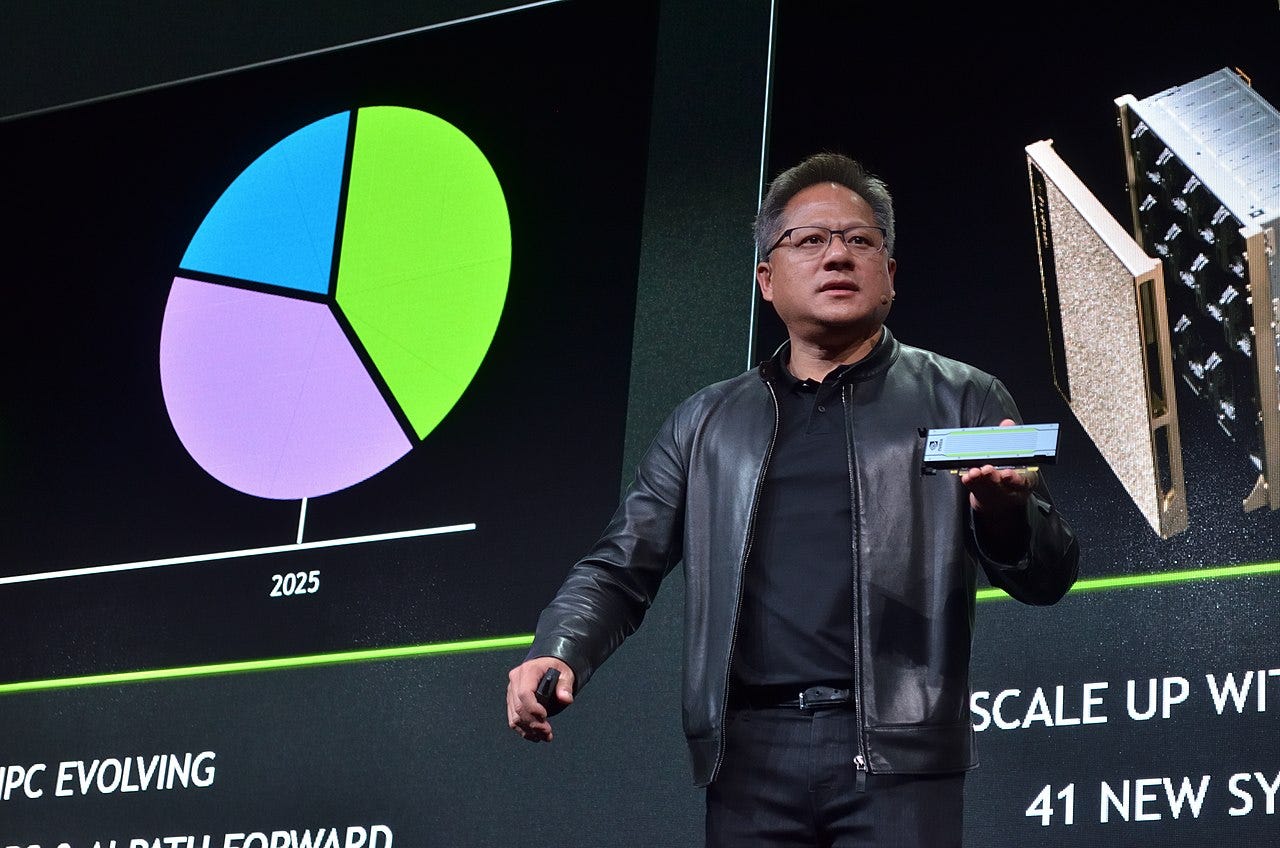

Nvidia does not manufacture its chips, instead being a “fabless” company focused solely on design and software. It outsources manufacturing to dedicated chip foundries that manufacture chips for designers, mainly to Taiwan’s TSMC and South Korea’s Samsung. While GPUs for gaming have been the company’s core product since the 1990s, Nvidia has shifted from providing GPUs for gaming to providing GPUs for computationally intensive AI algorithms. In the first quarter of 2021, Nvidia’s revenues from its “Data Center” vertical surpassed its gaming revenues for the first time.4 The company has also designed an increasing number of other kinds of computer chips, such as central processing units (CPUs) and data processing units (DPUs).

Nvidia’s shift from gaming to general purpose computing, especially for AI, has been architected by Nvidia’s cofounder and CEO Jensen Huang. The now 59-year-old Huang has led Nvidia as president and CEO since its founding in 1993. GPUs have properties that make them well-suited to run neural networks—a foundational technique for modern machine learning since 2012—and other computationally intensive algorithms. Huang realized the wider applicability of Nvidia’s technology relatively early on in the mid-2000s.

Since 2007, Nvidia has tied its hardware to a common software platform called Compute Unified Device Architecture (now commonly known as CUDA), which allows for GPUs to be easily programmed for general purpose computing and which has made it far easier for developers to build on each other’s work. Since then, this has essentially made Nvidia the bedrock of modern AI research. MLPerf, the standard for testing accelerated computing and setting benchmarks for training AI algorithms, is dominated by Nvidia.5

In terms of AI research, Nvidia has a significant profile, although far smaller than leaders like Meta, Google, and Microsoft. It ranks 17th for the number of AI publications, 15th for top AI conference publications, and 50th for AI patents.6 It won two best papers at the 2022 SIGGRAPH, one of the world’s most prestigious computer graphics conferences.7 Unlike larger companies like Google or Microsoft, Nvidia has not publicly made a major investment in a company focused on artificial general intelligence, such as DeepMind or OpenAI.

Rather than leading research in AI itself, Nvidia’s stated strategy is to become the provider for the hardware and software that other AI-dependent products and companies will use. According to Huang, he has staked Nvidia’s future on anticipating an industrial revolution built on computationally intensive automation that will remain centered around deep-learning neural networks and therefore will be structured around hardware in which Nvidia is currently dominant.8 Nvidia’s early and planned shift from gaming to AI is a strong indication that Jensen Huang is a live player capable of successful long-term strategy.

Nvidia’s strategy faces multiple challenges. The company’s position at the leading edge of computing technology makes the company vulnerable to fluctuations in optimism about emerging technologies, including AI, cryptocurrencies, robotics, or self-driving cars. Despite its entrenched position, much larger companies including Intel and Google are spending huge resources to wrest away their market share in computing hardware and software, though so far success against Nvidia has been limited.

But like most companies dependent on contractors in Asia, the largest challenge will be navigating the growing U.S.-China rivalry and the resulting export bans, trade wars, and other restrictions. As a fabless company, Nvidia is reliant mainly on Taiwan’s TSMC and South Korea’s Samsung to manufacture its chips. These two key relationships are not directly threatened by U.S. restrictions, but Nvidia, TSMC, and Samsung all rely on Chinese contractors for various services. For example, Nvidia notes Chinese companies such as BYD and Universal Scientific Industrial as subcontractors.9

While these contractors are most likely replaceable in the event of heightened restrictions, the revenue from sales of chips to China is not. Reportedly about a quarter of Nvidia’s revenue has come from China in recent years.10 With U.S. government decision-makers seeking to prevent exports of high-end chips to China, this revenue stream seems likely to stagnate or decline in the coming years. Regulators in the U.S., Europe, and China are all also becoming more hostile to mergers in the semiconductor industry, notably derailing Nvidia’s $40 billion attempt to purchase the British chip designer Arm in early 2022.

Overall, however, these are not existential threats to Nvidia. At 59, Jensen Huang will most likely continue to lead Nvidia for the next decade and is not yet facing a succession crisis. If Nvidia can maintain its relationships in Taiwan and South Korea, continue to design superior chips, and stay ahead of new U.S. challengers, Nvidia will be a tailwind for the AI industry as well as remain secure in its dominant position. As a relatively lean, but very well-resourced company led by a live player, Nvidia will most likely remain at the forefront of computing technology for the next decade.

The Primacy of CUDA

Nvidia designs GPUs, CPUs, and DPUs, which are sold either directly or as part of integrated products. Nvidia’s GPUs are the most important part of its business and are primarily sold as discrete units rather than integrated into CPUs, making them ideal for high-demand computing. Today, Nvidia dominates discrete GPUs with 79% of the global market for discrete GPUs in the first quarter of 2022.11 Nvidia also has 19% of the integrated GPU market, though Intel dominates integrated GPUs with about 60% of global market share.12 Both of these markets appear stable and consolidated.

Nvidia’s success is in large part due to its consistent technical skill at designing powerful GPUs. The more cores a GPU has, the more calculations it can process in parallel. With every new architecture for Nvidia’s chips, there are improvements in the number of cores and the number of transistors—the basic building blocks of computer chips that amplify or switch electrical signals. For example, in 2018 Nvidia’s Turing architecture improved on the 2016 Pascal architecture by increasing the number of cores from 4360 to 6912 and the number of transistors on the GPU from 19 billion to 54 billion. The 2022 H1 Hopper GPU, which uses the newest Hopper architecture and is specifically designed for high-end GPUs used in data centers, has 16,896 cores and 80 billion transistors.13

But while Nvidia has an advantage in designing powerful GPU hardware, its key strategic advantage is counterintuitively in software, through its CUDA platform. CUDA is an application programming interface (API) that allows software developers to easily program Nvidia GPUs for uses besides rendering graphics. This allows the high computing power of Nvidia’s GPUs to be used for machine learning, cryptography, molecular dynamics simulations, or anything else, with the caveat that CUDA is tied exclusively to Nvidia’s hardware.

As early as 2000, Jensen Huang had speculated that GPUs could be used for far more computationally intensive applications than just rendering graphics in video games.14 In November 2006, Nvidia announced CUDA. One of CUDA’s first handbooks from 2007 noted triumphantly that “in a matter of just a few years, the programmable graphics processor unit has evolved into an absolute computing workhorse.”15

Consistent improvement in GPU performance and the gradual popularization of CUDA eventually served as an effective platform for neural networks. Neural networks are a machine learning technique that is loosely based on neural models of the human brain. They are layered statistical models that apply weights to inputs and are built on matrices. They are incredibly data-intensive and so were considered for most of their history to be impractical.

The development of GPUs, which enable parallel processing of multiple data matrices, changed this. Neural networks became famous when researchers at the University of Toronto developed the AlexNet convolutional neural network in 2012. It was used in the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge and achieved error rates below any previous precedent.16 Since then, use cases for neural networks have vastly increased and have been heavily dependent on Nvidia’s CUDA platform.

Today, CUDA has been downloaded over 33 million times and has an ecosystem of roughly 3 million developers.17 Huang has argued that there are only three computers in the world: the Arm architectures, the x86 architectures originally designed by Intel, and Nvidia’s CUDA.18 Arm and x86 are the two main instruction set architectures upon which many chips are built. In contrast, CUDA is an expansive software platform for general-purpose computing with GPUs. Nvidia’s GPUs run on their own architectures, which are updated around every two years. Today CUDA is a staple for machine learning and proficiency in CUDA is insisted upon by many top AI recruiters.

The vast majority of wealth generated from these advances has flowed to large internet platforms, but as the singular provider of hardware and software to these platforms, Nvidia has an exceptional position. Its GPUs power eight out of the top ten supercomputers in the world, as well as almost 70% of the TOP500 list, which tracks the world’s top five hundred most powerful computers.19

Nvidia's share of hardware used for AI workloads across the major public cloud computing providers was 82% in June 2022, with Amazon’s custom chips for AWS coming in second with 8%.20 This market applies to training large AI data sets, where Nvidia is effectively a monopoly. Training refers to getting a program to learn through processing existing data sets. Inference, a more competitive market Nvidia is targeting, refers to applying the lessons of training to novel data.

CUDA has been expanded to include hundreds of libraries that are very popular for AI, with examples being CuDNN, Rapids, and Tensor RT. Nvidia has also written hundreds of software development kits (SDKs) that are tailored to specific industries. For example, Nvidia Isaac is an SDK focused on robotics. Major AI frameworks like Google’s TensorFlow, Meta’s PyTorch, and Microsoft CNTK are integrated into CUDA.21 The only comparable GPU development platform today, OpenCL, was originally developed by Apple and is now managed by the non-profit consortium Khronos Group. It is open-source, has different technical properties, and trades ease of use for being compatible with different hardware vendors.22

The proprietary barrier of only using Nvidia GPUs benefited the company greatly. It led to criticism from prominent open-source advocates like Linus Torvalds, the developer of the Linux operating system, who critiqued Nvidia’s lack of support for Linux, given its chips have benefited from the Linux-dependent Android operating system.23 Nvidia’s strategy with CUDA is similar to Apple’s highly successful strategy of tying software to proprietary hardware.

Both Apple and Nvidia have combined offshoring lower-margin segments of the supply chain, specifically manufacturing, to East Asia, while ferociously competing to control and monopolize design, computing, and software development. The combination of selective openness while controlling platforms typifies the most profitable companies of Silicon Valley and has proven a winning strategy for capturing value when a company can also in fact deliver on technical or design superiority.

Jensen Huang is a Live Player

With a 3.6% ownership stake in the company, Nvidia cofounder and CEO Jensen Huang’s net worth is estimated at $14.4 billion as of December 2022.24 Huang was born in Taiwan but grew up in the United States. He studied electrical engineering at Oregon State University and Stanford University. In 1985, he joined the semiconductor designer LSI Logic, while his future cofounders Curtis Priem and Chris Malachowsky were engineers at Sun Microsystems, a chip manufacturer and graphics developer. Sun Microsystems consulted LSI for much of its design innovation, with Huang being a high performer in this partnership.25

Nvidia got off to a strong start with three technically skilled founders with strong networks in Silicon Valley. In 1993, Huang convinced Priem and Malachowsky to set up a new fabless designer of hardware designed to meet the demand for 3D graphics in the nascent gaming industry, securing a $20 million round of funding led by Sequoia Capital the same year.26 Huang served as the CEO and the public face of the company, while Priem and Malachowsky held technical positions. Priem retired from Nvidia in 2003 while Malachowsky is still the Senior Vice President for Engineering.

Nvidia’s early years were made difficult by the sheer number of graphics providers and the company nearly went bankrupt in 1995.27 It was only with the 1999 development of the GeForce 256, the world’s first dedicated GPU, that it began to find success. The technology was novel and outperformed competitors by a wide margin. This was critical to Nvidia sealing a deal to supply Microsoft’s first game console, the Xbox. Nvidia also integrated as many non-manufacturing and distribution parts of the supply chain as possible. For example, most competitors used third parties to write device driver servers. Nvidia wrote its own, eventually achieving differentiation in quality.28

Importantly, Nvidia also developed a strong relationship with TSMC, which was rapidly becoming the most important foundry for semiconductors. Huang’s role in this was critical. He had experience in manufacturing chips while at LSI and understood the difficulty of succeeding at this while vertically integrating design and software development. Huang developed a friendship and partnership with the founder and CEO of TSMC Morris Chang, who had previously been a key executive at Texas Instruments before returning to Taiwan to found TSMC in 1987. For example, Huang called Chang directly in 1994 after failing to get a response from TSMC’s U.S. sales office.29

Consolidation and outsourcing allowed Nvidia to speed up its product cycle, sometimes releasing new architectures in less than six months.30 Nvidia’s ability to speed up its R&D cycle put huge downward pressure on GPU prices and ultimately collapsed many of the companies in the industry. As an example, Gigapixel was the company Nvidia outcompeted to supply cards to Microsoft’s Xbox, and it was subsequently acquired by 3DFX. In 2002, 3DFX itself was acquired by Nvidia.31

By 2002, Nvidia’s primary competitors in graphics were reduced to Canada’s ATI and Intel, the largest semiconductor company in the world. While Nvidia and ATI developed GPUs for high-performance needs, Intel relied on CPUs and integrated graphics into them. This gave them considerable market share for low-end graphics and forced Microsoft to end its own graphics business. But due to the limitations of CPUs compared to GPUs in parallel processing, the high-value end of the market, including video games and 3D animation, was monopolized by Nvidia and ATI. In 2006, ATI was acquired by AMD.

While Nvidia began shifting from video games to general purpose computing with CUDA’s introduction in 2007, it is only in 2022 that the majority of its revenue came from sources focused on high-level computing and AI, referred to as the “Data Center.”32 “Data Center” clients can include research institutes, enterprise customers, and independent developers, but are primarily large cloud computing vendors. The fifteen-year turnaround between the change in strategy and its ultimate success is a strong sign that Jensen Huang is a live player.

The “Data Center” segment has been growing in revenue at a compound annual growth rate of 66% from 2017 to 2022.33 To persist with this strategy implies a high degree of internal coherence at Nvidia and the achievement is more impressive when considering that Nvidia’s gaming revenues have grown at a very high rate as well. From 2017 to 2022, Nvidia’s gaming revenue grew at a compound annual growth rate of 25% from $4.1 billion to $12.5 billion.34

Nvidia retains a very strong advantage in software via its CUDA platform, but its advantages in hardware are abating relative to AMD and to a lesser extent Intel. The effectiveness of semiconductor manufacturers like TSMC and Samsung has also significantly lowered barriers to entry for different companies to design and produce their own specialized AI chips. The major chip designers are being challenged by both start-ups and very large technology companies like Google and Amazon, whose R&D budgets are comparable to Nvidia’s revenue.

Google’s Tensor Processing Units (TPUs) are a good example of the challenge Nvidia is up against. TPUs are application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs), are designed for AI inference and training, and are currently used in Google’s Cloud Platform and for services like YouTube.35 Elon Musk’s Tesla, previously reliant on Nvidia’s GPUs in its automobiles for the autopilot feature, built its own custom GPU in 2019 and replaced the use of Nvidia chips in its cars.36 Tesla still relies on Nvidia for training its systems and uses over seven thousand Nvidia GPUs for its private cloud.37 Lower barriers to entry into designing chips have led to a number of start-ups developing “AI chips” that seek to optimize deep learning the way GPUs optimized graphics. One example is Graphcore, a British company founded by Nigel Toon, a former employee of a company Nvidia acquired.

The amount of computing used in the largest AI training runs has been increasing exponentially, doubling every 3 to 4 months.38 Although relative value is tilting towards inference and embedded systems, data centers will continue to be a large growth market, pointing to Nvidia remaining a high-growth foundational company. It is likely that Nvidia’s monopoly in AI training cannot be maintained at its current level of 80%, but it does not need to. The GPU market was valued at $25 billion in 2020 but is predicted to grow to $250 billion by 2028.39

In 2022, the semiconductor market is globally worth $618 billion, with the single biggest market being for smartphones where Nvidia has a low footprint. By 2030, the revenue is projected to be $1.1 trillion, with the biggest market being data centers at $249 billion.40 Nvidia is dominant here and increasingly competitive in semiconductors for automobiles and industrial electronics, which are projected to grow in relative importance. If Nvidia can maintain just half its market share for the next 10 years, it could achieve revenues well in excess of $50 billion in a short period of time.

Antitrust and National Security Challenges

Nvidia’s future growth is challenged by the increasing attention governments pay to the semiconductor industry, both for antitrust and national security reasons. Semiconductors are a key “dual-use” technology which can be used for both civilian and military purposes and the U.S. government is increasingly attempting to prevent China from reaching the leading edge of chip technology. As a result it is becoming more difficult to make consequential acquisitions that consolidate the industry further.

Nvidia’s most ambitious acquisition attempt began in 2020 with a $40 billion deal to acquire British chip designer Arm from the Japanese conglomerate SoftBank. Arm’s licensees included potential rivals of Nvidia, like the U.S. Qualcomm, Europe’s STMicroelectronics, and China’s Huawei. The deal led to the perception that Nvidia was seeking monopoly status and immediately led to antitrust actions from multiple governments.

In 2021, the deal was reviewed by the British Competition and Markets Authority (CMA).41 In November of the same year, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) sued Nvidia to block the deal.42 Around the same time, the European Commission launched its own investigation citing similar concerns of anti-competitive behavior.43 Chinese authorities also rejected the deal.44 About 95% of the chips designed in China were Arm-based in 2018.45

Nvidia and Arm officially agreed to end the acquisition in 2022.46 This was not the first example of a merger in the semiconductor industry being stifled. Singapore-based Broadcom failed to merge with Qualcomm in 2018 due to resistance from the U.S. government.47 Qualcomm was blocked from acquiring Dutch NXP Semiconductor in 2018 due to Chinese obstruction.48

Governments have effectively placed a moratorium on large-scale vertical integrations and mergers within the semiconductor industry.49 The current ecosystem benefits the U.S. and its allies, and so any disruption to the status quo is likely to be received negatively. This limits acquisitions to buyouts of small vendors and startups. Partnerships between established players and large-scale acquisitions that add new products, as opposed to parts of the supply chain, are more acceptable, as shown by Nvidia’s successful acquisition of Israeli network equipment provider Mellanox or AMD’s $35 billion acquisition of American chip designer Xilinx in 2022.50

These were cases of acceptable “horizontal integration.” But vertical integration, besides consolidating resources, can upset other incumbents and cause uncertainty for governments, and so are blocked as much out of conservative instinct as concern for innovation. Nvidia can now redirect $40 billion to other projects and so is not significantly handicapped.51 But the failure of the deal does limit its ability to diversify towards embedded systems and mobile computing, an area in which it is not currently the market leader.52

As an American technology company that depends on East Asian manufacturing supply chains, Nvidia is also vulnerable to anti-China trade and manufacturing policies, which have accelerated under both the Trump and Biden administrations. For example, the extensive U.S. export restrictions on semiconductors to China, released in 2022, directly prevent Nvidia from selling its best chips to China, which makes up about a quarter of Nvidia’s revenue.53

Nvidia has responded faster than its competitors in developing a downgraded version of its A100 Tensor Core GPU that can still be sold to the Chinese market.54 The short timeframe between the sanctions and the rollout of the alternative suggests Nvidia is a live player, but even if Nvidia is better than its competitors at deriving revenue from China under restrictions, it can only be considered a short-term strategy to cushion the blows from export bans. As it is now restricted from selling its most sophisticated chips to China, its growth prospects weaken, though so do the growth prospects of any of Nvidia’s U.S. competitors.

Much like TSMC and Samsung, who are the main manufacturers of Nvidia’s chips, Nvidia relies on Chinese subcontractors for hardware and other services in its supply chain, for example specifically mentioning BYD and Universal Scientific Industrial in its 2022 report.55 Nvidia also relies on the Taiwanese contract manufacturer Foxconn for assembly. Foxconn’s largest facilities are in China, although it is also diversifying into India, Vietnam, and elsewhere.

Nvidia is therefore notably exposed to supply chain disruption or increased U.S.-China tensions, though its most important relationships with TSMC and Samsung are not threatened. The possible benefit of greater protectionism and export controls is increased support from the U.S. government through subsidies and other favorable policies for U.S. incumbents, but since Nvidia cannot offer domestic manufacturing, it is less well-positioned than a larger company that manufactures chips like Intel.

Nvidia does participate in U.S. government programs. In 2010, it received a $25 million grant from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to build supercomputers.56 It later received a further $20 million from DARPA in 2012 to develop low-power chips.57 Some of Nvidia’s biggest customers are nationally-funded supercomputers. Nvidia has worked with the U.S. government through an industry-university partnership with the University of Florida.58 But compared to Intel or other large corporations, its interaction with the government is limited.

Jensen Huang has an apparent disinterest in being a political player. He has no history of major political donations. While Nvidia is a member of the Semiconductor Industry Association, the primary trade body for American semiconductor companies, Huang is not on the board of directors. The Nvidia representative at the association is Tim Teter, the company's general counsel. In contrast, Pat Gelsinger and Lisa Su, the respective CEOs of Intel and AMD, are both board members.59

Huang has not shown an interest in retiring in the immediate future, so it will be left to him to deal with increasing political pressures. Nvidia reported no lobbying expenditures in 2022, compared to AMD spending $3.4 million60 and Intel spending $5.2 million.61 If Nvidia continues to grow as expected, Huang may be tempted to involve himself more directly in political matters. Huang has developed a significant industry reputation, but political patronage does not seem to be a preoccupation. He rarely if ever makes any political remarks, besides promoting his gratitude to the U.S. as a first-generation immigrant and optimism about technology.62

The Futures of AI and Nvidia Are Intertwined

A less tangible but possibly existential threat to Nvidia is that the hoped-for uses for AI in technology and industry never materialize. Huang has staked Nvidia’s long-term future on computationally intensive AI applications. But enthusiasm for technologies like self-driving cars and robotics can dissipate very rapidly. Other data-intensive areas, such as cryptocurrency, can be even more volatile.

Nvidia initially benefited from the cryptocurrency sector but was then negatively affected by the industry’s volatility. From 2009, Nvidia’s GPUs were considered a useful platform for the incredibly high demands of “mining” cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, where computational resources are expended to generate more units of a cryptocurrency. In 2017, Nvidia saw a large increase in demand for GPUs due to the massive increase in Bitcoin’s value. Nvidia tried to conceal the scale of its sales coming from demand for mining cryptocurrency, instead claiming the growth was attributable to gaming. In 2022, it was subsequently fined $5.5 million by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for misleading investors on this issue.63

The opportunity was always temporary. Large crypto-mining operations have shifted to more specialized ASICs and Nvidia is likely satisfied not to be a leader in an industry whose volatility can hurt it. The cryptocurrency Ethereum’s recent transition to a less computationally intensive model has recently reduced demand for GPUs, contributing to a decline in worldwide GPU prices which also hinders Nvidia.64

Most opportunities are more promising and less volatile than cryptocurrency, but there remains considerable uncertainty about their eventual value. While data centers will remain a growth market, autonomous vehicles have failed to develop much beyond pilot testing. Meanwhile, robots remain heavily localized in structured environments like factories and warehouses. While CUDA has expanded deep learning, it has not democratized its benefits away from large companies. True advances in deep learning are heavily concentrated and are reliant on institutional and intellectual dark matter that even most AI researchers are not privy to.65

While modern deep learning is good at setting benchmarks, practical applications like robotic manipulation of products have not been successfully commercialized. While CUDA remains the optimal platform to test the neural networks that might solve these problems, the possibility of stagnation could empower both large corporations and start-ups that seek alternative approaches to bringing large-scale automation to the market. But insofar as the computationally intensive deep learning model of AI is the most promising to usher in an AI revolution in technology and industry, Nvidia is one of the most promising companies poised to benefit from it.

Jensen Huang has shown an ability to undertake long-term, highly risky changes in strategy and achieve a massive payoff that places Nvidia at the center of a very promising market and justifies its enormous valuation. Increased governmental constraints through antitrust and export controls constrain Nvidia’s future vertical integration, but should not hinder its expansion based on its current model, so long as demand for powerful GPUs and other chips continues to increase. Nvidia’s enviable position is leading many would-be competitors to challenge it, but so long as Jensen Huang proves to be a live player while in charge of the company, Nvidia will probably be capable of weathering any competition, whether by simply outcompeting established giants or buying out small startup challengers.

“Top publicly traded semiconductor companies by market capitalization,” Companies Market Cap, accessed December 13, 2022, https://companiesmarketcap.com/semiconductors/largest-semiconductor-companies-by-market-cap/

Wallace Witkowski, “Videogames are a bigger industry than movies and North American sports combined, thanks to the pandemic,” MarketWatch, January 2, 2021, https://www.marketwatch.com/story/videogames-are-a-bigger-industry-than-sports-and-movies-combined-thanks-to-the-pandemic-11608654990

Nathan Benaich, Ian Hogarth, “Slide 52 – State of AI Report,” stateof.ai, October 11, 2022, https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1WrkeJ9-CjuotTXoa4ZZlB3UPBXpxe4B3FMs9R9tn34I/edit#slide=id.g164b1bac824_0_3663

Timothy Prickett Morgan, “Datacenter becomes Nvidia’s largest business,” Next Platform, May 26, 2022, https://www.nextplatform.com/2022/05/26/datacenter-becomes-nvidias-largest-business/

“AI Trifecta – MLPerf Issues Latest HPC, Training, and Tiny Benchmarks,” High-Performance Computing Wire, November 10, 2022, https://www.hpcwire.com/2022/11/10/ai-trifecta-mlperf-issues-latest-hpc-training-and-tiny-benchmarks/

“Private-sector AI-Related Activity Tracker,” Center for Security and Emerging Technology, 2022,

https://parat.cset.tech/

Rick Merritt, “At SIGGRAPH, NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang Illuminates Three Forces Sparking Graphics Revolution,” Nvidia Blogs, August 9, 2022, https://blogs.nvidia.com/blog/2022/08/09/siggraph-huang-metaverse-ai/

Jensen Huang, “The Intelligent Industrial Revolution,” Linkedin, November 30, 2016, https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/intelligent-industrial-revolution-jen-hsun-huang/

According to Nvidia’s 2022 annual report. See here: https://s22.q4cdn.com/364334381/files/doc_financials/2022/ar/2022-Annual-Review.pdf

According to BusinessQuant. See here: https://businessquant.com/nvidia-revenue-by-region-bill-to-location

Anthony Garreffa, “ GPU market share: NVIDIA commands with 80%, leaves AMD with 20%,” Tweaktown, September 5, 2022,

“PC graphics processing unit (GPU) shipment share worldwide from 2nd quarter 2009 to 1st quarter 2022, by vendor,” Statista, 2022,

https://www.statista.com/statistics/754557/worldwide-gpu-shipments-market-share-by-vendor/

“NVIDIA announces H100 Hopper GPU with up to 16896 FP32 cores, 80GB HBM3 memory, 700W of TDP,” Video Cardz, March 22, 2022, https://videocardz.com/press-release/nvidia-announces-h100-hopper-gpu-with-up-to-16896-fp32-cores-80gb-hbm3-memory-700w-of-tdp

“Hot 25: Jen-Hsun Huang,” EDN, December 20, 2000, https://www.edn.com/hot-25-jen-hsun-huang/

ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks, https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2012/file/c399862d3b9d6b76c8436e924a68c45b-Paper.pdf

“NVIDIA Introduces 60+ Updates to CUDA-X Libraries,” HPCWire, March 22, 2022, https://www.hpcwire.com/off-the-wire/nvidia-introduces-60-updates-to-cuda-x-libraries/

“Top supercomputers - June 2022,” Top 500 List, June 2022, https://top500.org/lists/top500/2022/06/

“Cloud Regions Map,” Liftr Insights, 2022, https://liftrinsights.com/cloud-regions-map

“Nvidia - Part 3: Beyond GPUs, Software Moat, and Competition,” Punchcard Investor, September 18, 2022, link.

Peter Zunitch, “CUDA vs. OpenCL vs. OpenGL,” Video Maker, 2022, https://www.videomaker.com/article/c15/19313-cuda-vs-opencl-vs-opengl

Vlad Savov, “Linus Torvalds: 'fuck you, Nvidia' for not supporting Linux,” The Verge, June 17, 2012, https://www.theverge.com/2012/6/17/3092829/linus-torvalds-fuck-you-nvidia

“Jensen Huang,” Forbes, 2022,

https://www.forbes.com/profile/jensen-huang-1/?sh=3ba53f763a6c

Andreas Bechtolsheim, Tom Westberg, Mark Insley, Jim Ludemann, Jen-Hsun Huang & Douglas Boyle, “Concept To System: How Sun Microsystems Created SPARCstationl Using LSI Logic’s ASIC System Technology,” Sun Microsystems, 1991, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4612-3192-9_27

According to Technology Magazine. See here: https://technologymagazine.com/ai-and-machine-learning/timeline-nvidia

“Nvidia: The GPU Company (1993-2006).” Acquired.fm, March 27, 2022, https://www.acquired.fm/episodes/nvidia-the-gpu-company-1993-2006

Michael Kanellos, “Nvidia buys out 3dfx graphics chip business,” CNET, April 11, 2002, https://www.cnet.com/culture/nvidia-buys-out-3dfx-graphics-chip-business/

Chris Coetting, “NVIDIA Q2 Earnings Show Strong Data Center Growth Undercut By Huge Gaming Slide,” Hot Hardware, August 24, 2022, https://hothardware.com/news/nvidia-q2-earnings-data-center-growth-gaming-slide

“Nvidia - Part 2: The Data Center is the New Computing Unit,” Punch Card Investor, May 14, 2022, link.

ASICs like this are more specialized than GPU-based solutions and so have potentially higher speeds. Their drawback is that they are less adaptable and require more expertise to use. The TPUs are optimized for Google’s own Tensorflow framework, while Nvidia’s CUDA allows for use of multiple AI frameworks.

Larry Dignan, “Nvidia takes aim at Tesla's custom GPU claims,” ZD Net, April 23, 2019, https://www.zdnet.com/article/nvidia-takes-aim-at-teslas-custom-gpu-claims/

Nathan Benaich, Ian Hogarth, “Slide 57 – State of AI Report,” stateof.ai, October 11, 2022, https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1WrkeJ9-CjuotTXoa4ZZlB3UPBXpxe4B3FMs9R9tn34I/edit#slide=id.g164b1bac824_0_3663; Danny Shapiro, “Tesla Unveils Top AV Training Supercomputer Powered by NVIDIA A100 GPUs,” Nvidia Blogs, June 22, 2021, https://blogs.nvidia.com/blog/2021/06/22/tesla-av-training-supercomputer-nvidia-a100-gpus/

“AI and Compute,” Open AI, May 16, 2018, https://openai.com/blog/ai-and-compute/

“Graphics processing unit (GPU) market size worldwide in 2020 and 2028,” Statista, October 1, 2021, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1166028/gpu-market-size-worldwide/

Dylan Patel, “ASML & The Semiconductor Market In 2025 & 2030,” Semianalysis, November 22, 2022, link.

“NVIDIA – Arm: Summary of the CMA’s report to the Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport on the anticipated acquisition by NVIDIA Corporation of Arm Limited,” Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, August 20, 2021, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/summary-of-the-cmas-report-to-the-secretary-of-state-for-digital-culture-media-sport-on-the-anticipated-acquisition-by-nvidia-corporation-of-arm/nvidia-arm-summary-of-the-cmas-report-to-the-secretary-of-state-for-digital-culture-media-sport-on-the-anticipated-acquisition-by-nvidia-corpo

Tali Arbel, “ US government sues to block $40 billion Nvidia-Arm chip deal,” Associated Press, December 2, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/technology-business-lifestyle-europe-united-kingdom-d8d599c15b4f4e14e6f7b3f78d09ef07

“Mergers: Commission opens in-depth investigation into proposed acquisition of Arm by NVIDIA,” European Comission, October 27, 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_5624

Ian King, Giles Turner, Peter Elstrom, “Nvidia Quietly Prepares to Abandon $40 Billion Arm Bid,” Bloomberg, January 25, 2022, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-01-25/nvidia-is-said-to-quietly-prepare-to-abandon-takeover-of-arm?sref=ZqW0mZJf

“Establishment of Joint Venture for China Business at Subsidiary Arm,” Softbank Group, June 5, 2018, https://group.softbank/en/news/press/20180605

Agam Shah, “'We gave it our best shot' Nvidia CEO tells Wall Street after failed Arm deal,” The Register, February 17, 2022, https://www.theregister.com/2022/02/17/nvidia_q4_fy2022_arm/

“Timeline: Broadcom-Qualcomm saga comes to an abrupt end,” Reuters, March 14, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-qualcomm-m-a-broadcom-timeline-idUSKCN1GQ22N

Michael Martina, Stephen Nellis, “Qualcomm ends $44 billion NXP bid after failing to win China approval,” Reuters, July 25, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-nxp-semicondtrs-m-a-qualcomm-idUSKBN1KF193

Stefan Modrich, Joseph Williams, “Semiconductor M&A activity challenged amid regulatory pressures,” S&P Global, August 3, 2022, https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/semiconductor-m-a-activity-challenged-amid-regulatory-pressures-70919487

Dave Altavilla, “AMD Completes Xilinx Acquisition And The Obvious Synergies Spell Great Potential,” Forbes, February 14, 2022, https://www.forbes.com/sites/davealtavilla/2022/02/14/amd-completes-xilinx-acquisition-and-the-obvious-synergies-spell-great-potential/

Ron Miller,” If the $40B Nvidia-Arm deal is dead, what does it mean to big tech M&A?” Tech Crunch, January 25, 2022, https://techcrunch.com/2022/01/25/if-the-40b-nvidia-arm-deal-is-dead-what-does-it-mean-to-big-tech-ma/

Peter Brown, “How Nvidia acquiring Arm could completely transform the chip industry,” Electronics 360, September 30, 2020, https://electronics360.globalspec.com/article/15747/how-nvidia-acquiring-arm-could-completely-transform-the-chip-industry

Philip Pilkington, “The shape of the chip market in the wake of the Chinese ban,” Macrocosm, November 9, 2022, link.

“Funding Round - NVIDIA.” Crunchbase, 2022, https://www.crunchbase.com/funding_round/nvidia-grant--d309aaef

Andrew Sadauskas, “NVidia wins $US20 million DARPA grant to supercharge low-power computing,” Smart Company, December 12, 2012, https://www.smartcompany.com.au/technology/emerging-technology/nvidia-wins-us20-million-darpa-grant-to-supercharge-low-power-computing/

Hodan Omaar, “ Industry-University Partnerships to Create AI Universities: A Model to Spur US Innovation and Competitiveness in AI,” Information Technology & Innovation Foundation, July 19, 2022, https://itif.org/publications/2022/07/19/industry-university-partnerships-to-create-ai-universities/

“Board of Directors,” Semiconductor Industries Association, 2022, https://www.semiconductors.org/about/board-of-directors/

“Advanced Micro Devices,” Open Secrets, 2022, https://www.opensecrets.org/orgs/advanced-micro-devices/summary?id=D000023765

“Intel,” Open Secrets, 2022, https://www.opensecrets.org/orgs/intel-corp/summary?id=D000000804

Isha Salian, “NVIDIA CEO Awarded Lifetime Achievement Accolade by Asian American Engineer of the Year,” Nvidia Blogs, July 18, 2021, https://blogs.nvidia.com/blog/2021/07/18/ceo-jensen-huang-awarded-lifetime-achievement-asian-american-engineer/

Andrew Cunnigham, “Nvidia hid how many GPUs it was selling to cryptocurrency miners, says SEC,” Ars Technica, May 6, 2022, https://arstechnica.com/gaming/2022/05/sec-fines-nvidia-5-5m-for-misleading-investors-about-gpu-sales-to-crypto-miners/

Kyle Orland, “ The end of Ethereum mining could be a bonanza for GPU shoppers,” Ars Technica, September 16, 2022, https://arstechnica.com/gaming/2022/09/the-end-of-ethereum-mining-could-be-a-bonanza-for-gpu-shoppers/

Rich Sutton, “The Bitter Lesson,” Incomplete Ideas, March 13, 2019, http://www.incompleteideas.net/IncIdeas/BitterLesson.html