The Functionality of DARPA is Politically Precarious

After sixty years, the R&D agency is still exceptionally functional. But government leaders do not understand how to replicate its success, nor the unique autonomy that underpins it.

The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is likely the most well-known R&D agency in history. Founded in 1958, it is an agency within the U.S. Department of Defense, responsible for leading the development of technologies that maintain and advance the capabilities and technological superiority of the U.S. military. DARPA’s innovations are numerous: it has played a key role in developing both explicitly military technologies like stealth aircraft, precision-guided munitions, and drones, as well as civilian technologies, from semiconductors and superalloys to, famously, the graphical user interface (GUI) and ARPANET, the predecessor of the modern internet. Despite a long list of wins, DARPA is an exceptionally small organization. For the financial year 2023, the budget request for DARPA was just $4.1 billion, roughly 0.5% of the Defense Department’s $773 billion budget request for the year.1 The organization’s staff count has historically been kept very low at about one hundred to two hundred people.

You can listen to this Brief in full with the audio player below:

DARPA has been a highly effective R&D agency since its inception because of its unique internal structure which empowers “program managers” with wide autonomy to create, fund, and discontinue research projects. DARPA doesn’t actually do any research itself: its program managers just award and control funding to outside researchers at companies, universities, and non-profits. But DARPA’s unique contribution is being a steady source of funding for speculative and experimental research, the results of which individual program managers are allowed to judge on their own without going through committees or peer review.

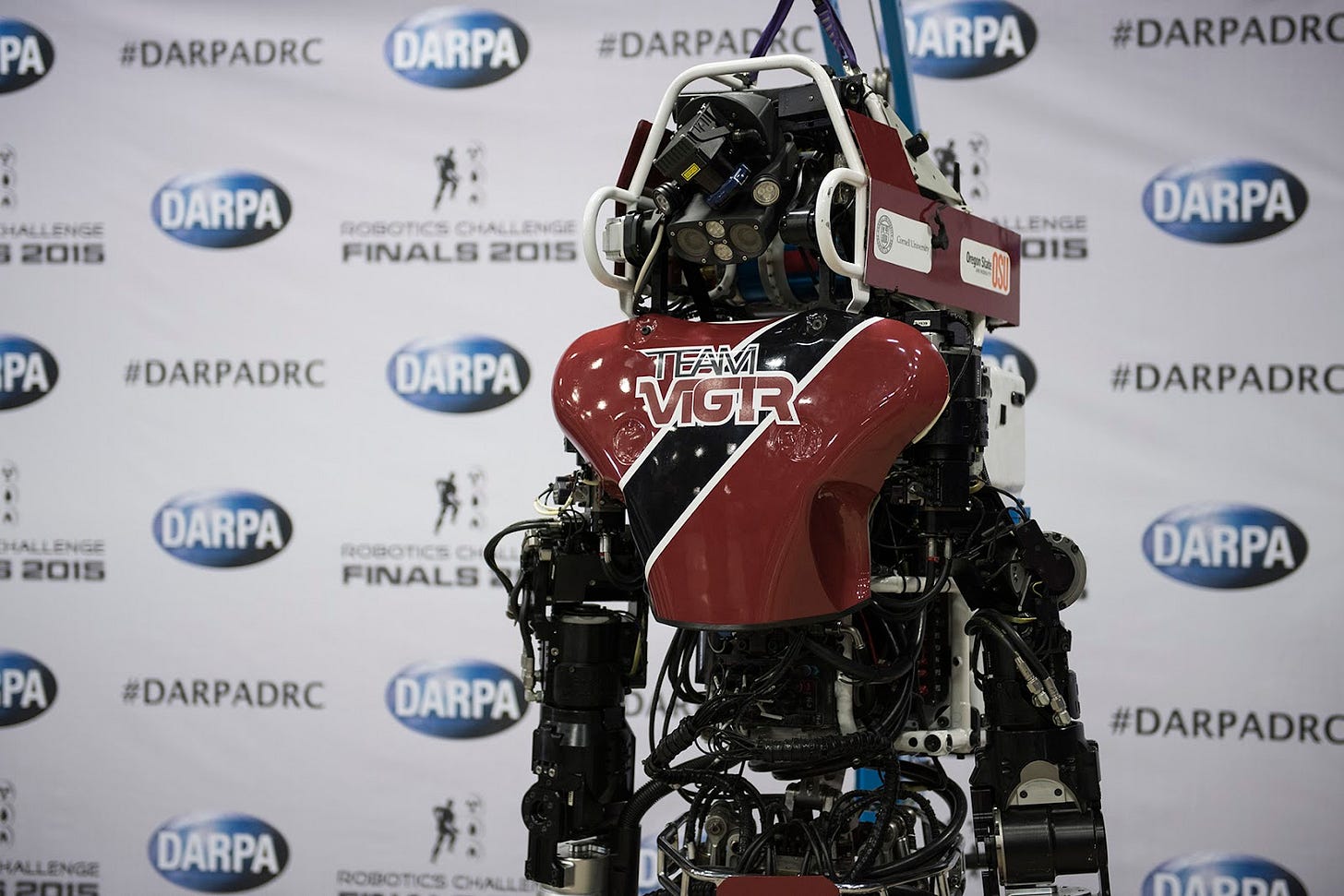

As a result, with over sixty years of eclectic and high-variance projects funded, DARPA can take at least partial credit for almost any technological advance since the 1950s, including in quantum computing, robotics, and even photovoltaic solar panels. The agency was founded with the personal support of President Dwight Eisenhower against the established bureaucracies of the military, in the context of a perceived crisis of technological innovation caused by the Soviet Union’s launch of Sputnik, the first artificial satellite in Earth’s orbit. But DARPA’s autonomy has been slowly eroding since its founding. For example, in 1972 DARPA got its current name—it was founded as merely the Advanced Research Projects Agency, or ARPA—and was prohibited by Congress from spending funds on research without a direct military application.

Nevertheless, despite a shift towards more research in aerospace and armaments, DARPA would continue to fund a wide variety of projects and defend its autonomy by making more projects classified or by simply giving increasingly elaborate justifications for the military applications of a project. For example, in 2006 DARPA justified funding for solar panel efficiency research on the grounds that it could eventually help soldiers carry less batteries for equipment on the battlefield.2 This is a somewhat tenuous justification for direct military application compared to funding more breakthroughs in missiles or aircraft, but this kind of creative thinking has prevented DARPA from becoming just another military R&D program.

The agency’s reputation is strong enough that several attempts have been made to found institutions imitating DARPA. The U.S. government has now ostensibly created variants of DARPA specifically focused on energy, intelligence, and health, while the governments of Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, and even Russia have created imitations of DARPA. Well-capitalized private companies have also attempted to use DARPA as a model, with Google hiring former DARPA director Regina Dugan in 2012 to launch Google’s Advanced Technology and Projects (ATAP) group.

While the proliferation of imitators is a compliment to DARPA’s accumulated prestige, none of them demonstrate a clear understanding of the internal structure that made DARPA’s successes possible. This same lack of understanding is increasingly afflicting DARPA as well, which finds itself pressured by the wider U.S. government to redirect research efforts into politically urgent causes like artificial intelligence, vaccines, or securing U.S. military supply chains.

DARPA’s functionality is based precisely in the ability of its program managers to determine which research projects to pursue, rather than their superiors or even national government leadership. The less political leaders understand this and try to change DARPA’s research priorities as a result, the more they reduce DARPA’s unique functionality. DARPA’s prolific willingness to fund speculative and basic research on new technologies has arguably made it the main driving force behind U.S. industrial policy since the 1960s, since every new technology is also a potentially transformative new industry.

DARPA’s role in the creation of the internet is a case in point: under the leadership of the computer scientists J. C. R. Licklider, Bob Taylor, and Larry Roberts, DARPA ran numerous projects in the 1960s to create a nationwide computer network, which would eventually result in ARPANET, the precursor to the modern internet. According to Taylor, they were hardly attempting to meet specific military goals, but just excited about the possibility of “man-computer symbiosis,” which was also the title of a 1960 paper by Licklider.3 Taylor had arranged funding for the inventor Douglas Engelbart to invent the computer mouse before he had even joined DARPA.4 The initial funding for ARPANET was $1 million transferred out of the agency’s ballistic missile budget on the strength of Taylor’s proposal to the DARPA director.5

This role is fundamentally at odds with the desires of political and military leadership outside of DARPA, who increasingly want DARPA to provide breakthrough technological solutions to their relatively more mundane political or logistical problems. DARPA can and will likely continue to deliver technological progress due to its continuing internal autonomy for program managers, even if its overall research priorities are increasingly shaped by outside forces. But the less genuine autonomy DARPA has, the less likely it is to precipitate another transformative technology and industry.

DARPA’s Model Depends on Empowering Program Managers

DARPA’s budget is allocated under the wider Department of Defense (DoD) budget, with congressional oversight over individual projects. It is one of many research organizations under the DoD.6 Its presence in the wider U.S. government defense science and technology budget has recently been steady at between 21% and 25% from 2000 to 2021.7 DARPA’s share of the “Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation” budget for the DoD has markedly dropped from 6.4% in 1996 to 3.3% in 2021.8

The funding is split between four categories: basic research, applied research, advanced technology development, and management support.9 The ratio of funding spent on each category has remained largely the same since 1996, though basic research has increased somewhat at the expense of advanced technology development.10 DARPA’s personnel count is exceptionally small at around 220 people in 2022, just enough for everyone to know each other's names.11

DARPA is currently subdivided into six technical offices: the Biological Technologies Office, the Defense Sciences Office, the Information Innovation Office, the Microsystems Technology Office, the Strategic Technology Office, and the Tactical Technology Office. DARPA also occasionally creates temporary special projects offices focused on coordinating with the DoD to integrate technology into military practice and doctrine. Live temporary projects include the Aerospace Projects Office and the Adaptive Capabilities Office. Each office is assigned a director who oversees a number of program managers. These office directors report to the organization’s overall director. The organization is overwhelmingly staffed with personnel from the armed forces, national laboratories, and defense procurement offices, most of whom have a doctorate.

DARPA’s structure necessarily leads to a high variance in outcomes. Individual program managers lead their projects and have a high degree of autonomy on whether to continue funding or wind down a project. They are not required to seek peer review for the project’s progress from other managers. The lack of a review panel is a stark contrast to similar government research organizations like, for example, the National Science Foundation (NSF), which had a much larger budget of $8.8 billion in 2022 and employs nearly two thousand people.12

Program managers have a high level of autonomy. They generate ideas for projects and have a high level of authority over project partners. They only need initial approval for a project and have autonomy in allocating or withdrawing funds. Program managers have only one official checkpoint with their office directors before launching programs and their ability to move money around quickly gives them leverage over research partners.13 This system of manager-led control works in the context of DARPA’s ultimately exploratory mission.

Initial funding of a DARPA program can vary but is generally over $1 million.14 Most of this money goes towards smaller contracts designed to help solidify that an idea is first not impossible and second that it is possible within scope. These investments can be as low as $50,000 and last up to nine months.15 They are designed to keep the rate of failure acceptably low and keep the scope of research narrow and focused. It is also a striking example of an institution designed in such a way as to conduct experimental science.

Program managers are generally not obligated to go through any type of peer review, but they do rely on their own informal networks of technical experts to determine the viability of their programs.16 They are also able to bring on contractors from outside to assist them in project management. These contractors are subordinate to the program manager, but there is sufficient institutional trust in DARPA to allow them significant autonomy and even the ability to liaise between different programs. As a result, part of the program manager’s job is to skillfully find, evaluate, and communicate with the right technical experts and contractors, then delegate the right problems to them.

Short tenures are also critical. Program managers have a tenure of between three to five years, with many leaving after just one year. In most types of organizations, this huge downward pressure on institutional memory would be a major inhibition to functionality. But much like Israel’s Unit 8200, DARPA’s exploratory mission counterintuitively benefits from this short tenure. Moving personnel in and out of DARPA increases the number of DARPA alumni and thus the organization’s informal network of experts, a key resource for program managers.

Short tenures can lead to the repetition of failed programs due to the lack of institutional memory. But this predictable turnover of program managers every few years actually means that even if a project idea is repeated, material circumstances in the world have likely changed and might make previously unviable projects viable due to advances in other technological fields. While the repetition of old failures may seem dysfunctional, it keeps the possibility of breakthrough success open.

Limited tenure creates a culture of urgency where managers do not wait to end projects they feel will not make an impact. The practice of transient tenure was only codified in the 1990s because many program managers were staying for longer. The short tenures also discourage the desire to build bureaucratic centers of power or large budgets.

The system is unusually high-trust and therefore dependent both on highly skilled program managers, who can be hired from anywhere, and office directors willing to give them real autonomy. The tolerance for failure, the promise of interesting work, high autonomy, and limited tenure as well as access to DoD leadership have historically made DARPA an appealing prospect for high-quality managers.

To enable this further, in 1998 the U.S. Congress’ annual National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) granted DARPA the authority to hire up to 25 personnel from outside the federal government for up to six years without being restricted by established codes for qualifications and compensation of civilian government employees.17 Over the years, this authority was routinely reapproved and the cap raised. It was made permanent in 2017 and the cap on the number of such hires raised from 100 to 140. In other words, enough to make most personnel at DARPA institutional outsiders, though it's unclear how much of this is utilized.

The NDAAs have also been used to expand discretionary procurement. The 1990 NDAA provided DARPA with “other transactions” (OT) authority, which grants it exemption from government procurement rules. This is designed to enable procurement partnerships with companies that want to avoid standard procurement regulations. DARPA is far from the only organization that has this authority.18 From 2010 to 2014, the vast majority of OT transaction agreements applied to NASA. Given the limited progress of NASA in that time, however, streamlined procurement does not imply functionality, though in this case it may have helped Elon Musk’s SpaceX.

Being a DARPA program manager is not financially rewarding. In 2017, salaries were estimated at $90,000, far less than comparable positions in the private sector.19 The gap between a DARPA salary and private sector pay has widened since 1958 due to increased opportunities in computing and software. There is no promotion within DARPA and any achievements at the project level are concealed by security clearance, limiting the personal value of projects to program managers in the wider job market. However, being an employee of DARPA, no matter how temporary, brings with it a prestige that translates into a good reputation within a given area of expertise.

Externalizing the actual research to other organizations comes with many advantages. It allows DARPA to remain a small and simple organization. A lot of cutting edge research is dependent on bespoke equipment and unique traditions of knowledge that cannot be replicated and are isolated in one or two locations, such as a particular university-affiliated research laboratory or specialized firm. Such assets would be difficult to integrate and expensive to acquire permanently.

It also makes a single program manager accountable and legible to their superiors and maximizes the autonomy and freedom of the program manager to distribute funds. In 2020, 62% of R&D obligations went to industrial recipients, with the rest going to universities and non-profits, and a small number going to foreign recipients.20

Program managers are still reliant on the patronage of their office directors and the director of DARPA as a whole. The outlook and views of the director can have huge implications for the organization. Directors may not allow managers to be autonomous if they are being pressured by external actors, or they may have their own particular interests. While managers are empowered at DARPA, their power is ultimately borrowed and dependent on their office directors and the agency director.

Program managers can in some cases become directors, as was the case with Regina Dugan, who was the director from 2009 to 2012. She became noteworthy for extolling DARPA in public media, as well as for causing violations of ethics regulations.21 Dugan would later found DARPA-like organizations in the private sector, such as Google’s Advanced Technology and Projects (ATAP).

DARPA has proven capable of making breakthroughs other agencies cannot, but it is not completely insulated from failures in the Department of Defense. If a major program has the blessing of the armed forces, the DARPA director cannot approve projects without considering their value to the DoD’s goals. DARPA’s quality of programs was, for example, affected by the Vietnam War. The DoD’s Future Combat System (FCS) project also heavily influenced DARPA’s foray into robotics development. So while DARPA can produce novel research, it is not a complete substitute for an effective military bureaucracy.

The Slowly Decaying Autonomy of DARPA

DARPA was founded in an institutional panic. Prior to the 1957 launch of the Soviet satellite Sputnik, the first artificial satellite in Earth’s orbit, U.S. officials were confident about American technological superiority over the Soviet Union. The Sputnik demonstration caused a high degree of embarrassment within the Eisenhower administration and led to many new institutions, of which ARPA—DARPA’s original name—was just one.22 For example, NASA was also founded as a result in July 1958.

The creation of DARPA was driven from the top by U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower, who was able to surround himself with like-minded advisors and allies in the White House. For example, from 1957 to 1959, the president of MIT James R. Killian served as Eisenhower’s presidential science advisor. Killian was a proponent of giving scientists more authority on their research projects, as opposed to taking direction from the military. Killian at various hearings championed high tolerance for failures, non-hierarchical management, independence from non-technical military personnel, and externalization of research. All of these would become foundational principles of DARPA.

DARPA’s founding was opposed by the various branches of the military, as its novel program implicitly criticized their approaches. But Eisenhower had both experience and exasperation with military bureaucracy. A career U.S. Army officer, he had overseen the U.S. invasion of Europe during World War II as a five-star general, and held the position of the first Supreme Commander of NATO military forces in Europe before being elected to the U.S. presidency. Only four days after Sputnik’s launch in October 1957, Eisenhower appointed the president of consumer goods manufacturing giant Procter & Gamble, Neil H. McElroy, to the role of Secretary of Defense. By November, McElroy had announced the creation of a new organization called ARPA.

McElroy had no experience in government and, as a new cabinet member, was not aligned with the military, but rather only with Eisenhower personally. Rebuttals from the Pentagon affected the parameters of ARPA, which in turn made it smaller and focused more on externalizing research. Eisenhower himself approved of the project more the more resistance it caused within the military. DARPA’s founding, then, occurred in a very short period of time and was dependent on a number of unique factors working together: scientists having direct access to the president, a new defense secretary without any institutional loyalty to the military bureaucracy, and a determined president who was exasperated with the military establishment that he knew very well, and against which he used the perceived crisis of the Sputnik launch.

DARPA, like any organization, has changed since 1958. But the consistent trend has been towards more explicit processes and direction, less opacity, and greater definition of roles. The shift from ARPA to DARPA in 1972 was due to the external pressure of the Vietnam War. In 1969, Senator Mike Mansfield pushed an amendment to the annual military spending bill that expressly prohibited funding research that lacked “a direct and apparent relationship to a specific military function.”23 Another amendment in 1973 expressly limited DARPA in the same way.

While the DoD does not have authority over the specific programs being targeted, it can pressure the DARPA director to focus on specific areas aligned with the U.S. military’s current operations. For example, during the Vietnam war, ARPA was pushed into focusing on jungle warfare. This led to bizarre failures including a robotic quadruped mimicking an elephant.24 So while the director lacks a high degree of direct oversight over program managers, the director is critical to avoiding DARPA’s politicization or normalization into a more traditional DoD agency.

DARPA’s own official website acknowledges arguments that, based on the company’s output, its best days were between 1958 and 1972, before its mission became officially solely military.25 The directorship of career engineer George H. Heilmeier saw the implementation of the “Heilmeier catechism” in 1975: a series of questions used to determine a project’s viability, which remains in use today.26 This was criticized by people like J. C. R. Licklider, who had worked for ARPA prior to 1972.27

In response to increased congressional oversight, DARPA made more of its projects classified. Program managers would argue a degree of opacity was the price to pay for DARPA’s exceptional output. Presidents have regularly replaced DARPA directors upon entering office and since 2001 the DARPA directorship became aligned with presidential administrations. In 2001, the rule around who could be a prime contractor shifted from any organization to large companies.28

DARPA has been openly criticized by legislators. In 2003, two Democratic senators excoriated the organization over the Policy Analysis Market (PAM) program, a forerunner to prediction markets that sought to predict likely terrorist attacks. They argued it represented a stomach-churning and speculative terror market.29 The project was abruptly canceled following a media storm. The $1 million grant was easy to drop. PAM was a product of the Information Awareness Office (IAO), which was run by John Poindexter, a career naval officer and President Ronald Reagan’s former National Security Advisor.

Poindexter resigned following the shutdown of PAM. This episode showed DARPA could not insulate itself entirely from public perceptions or congressional scrutiny. It also showed how greater transparency in the face of lawmakers conflicted with risky and previously secretive research which could nevertheless be transformative. PAM did foster research that eventually led to the mainstreaming of prediction markets.

DARPA has also come under the scrutiny of bioethicists. The Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues recommended that institutions supporting neuroscience research integrate ethical considerations early on and explicitly throughout a research project. DARPA addressed the integration of ethical considerations into its work by requiring neuroscience research program managers to engage an independent “Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications” panel at the start of a project.

A Proliferation of Imitators

Attempts to replicate DARPA’s model have been made both in the U.S. and abroad. The two notable U.S. examples are IARPA (intelligence) and ARPA-E (energy). IARPA reports to the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI). It was created in 2006 and consolidated the resources of the National Security Agency's Disruptive Technology Office, the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency's National Technology Alliance, and the CIA’s Intelligence Technology Innovation Center.

IARPA is most notable for funding U.S. quantum computing research heavily between 2007 and 2010. In so doing it had been carrying on the work of DARPA, which was involved in quantum technology from an early stage.30 IARPA is considerably smaller than DARPA, with only twenty-three employees in total and nineteen program managers.31 IARPA does not pursue commercialization and is wholly focused on programs for the U.S. intelligence community. Despite this, the vast majority of IARPA projects are unclassified and many have researchers in foreign jurisdictions.

ARPA-E was set up in 2009 as part of the America COMPETES Act and reports to the U.S. Department of Energy.32 Its programs are split between electricity generation, grids and storage, efficiency & emissions, and transportation & storage.33 ARPA-E was immediately disadvantaged by the highly specific mission of the Department of Energy. As of 2022, it had fifteen program directors performing the roles of program managers.34 While IARPA is exclusively focused on the intelligence community as a potential client, ARPA-E is focused on private companies to scale its output.

Unlike DARPA, ARPA-E has in-house commercialization resources designed to bring its technologies to market, including a legal department. There is a formal process in ARPA-E distinct from DARPA, including quarterly written reports from researchers to program directors. These formalized reports are less hands-off than DARPA’s.35 Project proposals can be vetoed against the wishes of program directors. While DARPA is funded by Congress, the Department of Energy gets the ultimate say in how much money is allocated to ARPA-E.

In recent years, several countries have spun up their own DARPA imitators. In 2012, Russia established the Advanced Research Foundation, which is nominally analogous to DARPA.36 But there is no indication it emulates the flat structure or program manager-led research.37 In 2018, the German government created the Agency for Innovation in Cybersecurity, followed in 2020 by the Federal Agency for Disruptive Innovation (SPRIND), a limited liability corporation focused explicitly on non-military research.

In 2019, the Japan Science and Technology Agency launched the Moonshot R&D Program. Its funding is allocated based on targets and goals set by a “visionary committee.”38 In both the case of Moonshot and SPRIND, the remit of research is specifically focused on society’s betterment, with safety, privacy, sustainability, and mitigating the challenges of an aging population particularly emphasized.

In 2022, the United Kingdom set up the Advanced Research and Innovation Agency (ARIA). On paper, it matches the original ARPA model of a flat organization, empowered program managers, tolerance for failure, and externalized research. It also harks back to the pre-1972 days when ARPA was not explicitly focused on military applications. ARIA reports to the Department of Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy. Its budget is independent of standard government funding.

While the British agency is perhaps the most promising, both the U.S. and foreign imitators seem to miss the key elements that made DARPA successful in the first place. When projects are loaded with normative political positions, their success or failure becomes more critical for internal stakeholders, especially if normative political positions are polarizing. DARPA has been criticized for opacity and amorality, but this was critical to building such an intellectually productive environment. It is noteworthy that for Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom, these initiatives have all occurred in a recent time frame between 2019 and 2022. These are all U.S.-aligned countries that face varying degrees of declining economic and industrial dynamism, so these DARPA imitators are being marketed as part of a broader push to move up the value chain and become more research-intensive.

The Agency’s Present and Future Priorities

DARPA today still retains a very broad focus, with many projects related to military technologies in aerospace and armaments, such as new forms of propulsion, as well as fields like biotechnology and AI. But in recent years there has been increased emphasis on new manufacturing techniques, improving state capacity, and delving into the social sciences to respond to “undergoverned spaces” and hybrid warfare. This expanded remit exists in the context of increased and often indeterminate geopolitical competition with few well defined aims. Internal documents from DARPA’s Defense Sciences Office—whose mission DARPA describes as “highly exploratory”39—stress the return of peer-to-peer competition with China and, to a lesser extent, Russia.40

Among projects today, there is also plenty of interest in improving governance through automating compliance with complex, overlapping policies and regulations.41 Increased attention is also being paid to geopolitical questions like supply chains for key chemicals. In one program slide, for example, a key sedative that saw increased demand during the COVID-19 pandemic was singled out for having a highly vulnerable supply chain. This also applies to military chemicals like HTPB, a chemical critical for various rocket fuels. One of DARPA’s programs is to hypothesize how they could quickly develop and automate new supply chains in the event of disruption for these critical materials.

DARPA’s focus is becoming more clearly impacted by external pressures like the COVID-19 pandemic. Matthew Hepburn, the DoD vaccine lead for Operation Warp Speed, had previously been a program manager at DARPA.42 The mRNA delivery systems that were critical to vaccine development were initially funded by DARPA through the program ADEPT:PROTECT in 2010, led by the Air Force doctor and program manager Dan Wattendorf.

In 2013, DARPA made a $25 million grant to the recently founded biotech firm Moderna Therapeutics to advance promising antibody-producing drug candidates into preclinical testing and human clinical trials. The company would make vaccines using mRNA technology. Although DARPA could not scale this technology, it provided governments with a proven vaccine platform to turn to when it was most needed. This has led to calls for the development of an ARPA-H (health), which has since been approved. DARPA has also launched a number of projects centered around detection, testing, and prevention of diseases, as well as around manufacturing vaccines and essential supplies in the event of future pandemics.43

In 2018, DARPA launched a multiyear campaign called AI Next, which earmarks $2 billion for artificial intelligence related projects. AI Explore is a part of this campaign as an umbrella for a series of high-risk, high-payoff projects. DARPA projects have often failed due to lack of commercialization or insufficient opportunity to scale, but in the case of this push for AI, the DoD itself is being treated as a potential testing ground. Adoption within the bureaucracy is likely to be coordinated by DARPA teams and the newly founded Digital and Artificial Intelligence Office, which was formed in early 2022.44

These outside priorities are a mixed bag for DARPA’s potential impact. Despite the high saturation of research funding aside from DARPA, there are nevertheless likely important contributions to be made in funding research in artificial intelligence and biotechnology. But other things like securing supply chains, counterinsurgency, and projects assuming various sociological theories about U.S. adversaries seem driven more by outside pressure to make up for failures in industrial, economic, and foreign policy by the rest of the U.S. government, rather than transformative research intended to advance science and technology as per DARPA’s mission.

For decades, DARPA has nevertheless demonstrated a surprisingly strong ability to circumvent outside priorities in its mission to advance science and technology. Since 1972, incrementally growing restrictions on DARPA’s priorities have perhaps blunted its capacity to produce anything as transformative as the internet and personal computer. But it has not stopped progress in many other fields. The long-term risk for DARPA is that political and military leaders outside the agency fail to understand why DARPA works at all.

While such leaders believe in DARPA’s effectiveness, they do so without grasping what underpins it. As a result, they attempt to shape DARPA’s priorities towards their own, without understanding that such shaping is precisely what reduces DARPA’s functionality, by reducing the autonomy of program managers. For now, DARPA’s autonomy from the outside seems to be intact, so there is no reason to expect the agency to become dysfunctional in the short term. But as the U.S. faces growing economic, social, and political challenges in years to come, future government leadership might think further commanding DARPA’s priorities is a necessary step to solving those challenges. DARPA will stop being a functional institution if future program managers can no longer manage research at their own discretion.

“Budget,” DARPA, 2022, https://www.darpa.mil/about-us/budget.

D. Kirkpatrick, E. Eisenstadt and A. Haspert, "Darpa's Push for Photovoltaics," 2006 IEEE 4th World Conference on Photovoltaic Energy Conference, 2006, pp. 2556-2559, doi: 10.1109/WCPEC.2006.279767.

John Markoff, “Douglas C. Engelbart, 1925-2013: Computer Visionary Who Invented the Mouse,” The New York Times, July 3, 2013, https://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/04/technology/douglas-c-engelbart-inventor-of-the-computer-mouse-dies-at-88.html

Ibid.

“Organizations,” Department of Defense, 2022, https://www.defense.gov/Resources/Military-Departments/DOD-Websites/?category=Research+and+Development

“Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency: Overview and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Office, August 19, 2021, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/R45088.pdf

“Department of Defense Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation (RDT&E): Appropriations Structure,” Congressional Research Office, September 7, 2022, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44711/11

“Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency: Overview and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Office, August 19, 2021, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/R45088.pdf

“Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency: Overview and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Office, August 19, 2021, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/R45088.pdf

“NSF Budget: FY22 Outcomes and FY23 Request,” American Institute of Physics, April 13, 2022, https://www.aip.org/fyi/2022/nsf-budget-fy22-outcomes-and-fy23-request

Benjamin Reinhardt, “Why does DARPA work?” Personal Website, June 2020, https://benjaminreinhardt.com/wddw

Ibid.

Ibid.

According to interview with former DARPA contractor in robotics R&D, in personal correspondence with the analyst, October 2022.

“Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency: Overview and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, August 19, 2021, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/R45088.pdf

According to the GAO. See here: https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-16-209.pdf

Benjamin Reinhardt, “Why does DARPA work?” Personal Website, June 2020, https://benjaminreinhardt.com/wddw

“Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency: Overview and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Office, August 19, 2021, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/R45088.pdf

According to a report by the DoD Inspector General. See here: https://media.defense.gov/2018/Jul/24/2001946377/-1/-1/1/DUGANROI(REDACTED).PDF

“The Advanced Research Projects Agency 1958-1974,” Richard J. Barber Associates, October, 1975, https://documents2.theblackvault.com/documents/dtic/a154363.pdf

“The Mansfield Amendment,” The National Science Foundation, 2022, https://www.nsf.gov/nsb/documents/2000/nsb00215/nsb50/1970/mansfield.html

Michael Joseph Gross, “ The Pentagon's push to program soldiers’ brains,” The Atlantic, November, 2018 https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2018/11/the-pentagon-wants-to-weaponize-the-brain-what-could-go-wrong/570841/

“Timeline,” DARPA, 2022, https://www.darpa.mil/Timeline/index

“The Heilmeier Catechism,” DARPA, 2022, https://www.darpa.mil/work-with-us/heilmeier-catechism

Dominic Cummings, “#29 On the referendum & #4c on Expertise: On the ARPA/PARC ‘Dream Machine’, science funding, high performance, and UK national strategy,” Personal blog, September 11, 2018, https://dominiccummings.files.wordpress.com/2018/09/20180904-arpa-parc-paper1.pdf

Benjamin Reinhardt, “Why does DARPA work?” Personal Website, June 2020, https://benjaminreinhardt.com/wddw

Robin Hanson, “The Policy Analysis Market: A Thwarted Experiment in the Use of Prediction Markets for Public Policy,” Innovations Journal, 2007, https://direct.mit.edu/itgg/article/2/3/73/9498/The-Policy-Analysis-Market-A-Thwarted-Experiment

Chipp Elliot, “The DARPA Quantum Network,” BBN Technologies, 2022, https://arxiv.org/ftp/quant-ph/papers/0412/0412029.pdf

“Leadership,” IARPA, 2022, https://www.iarpa.gov/who-we-are/leadership

“America Creating Opportunities to Meaningfully Promote Excellence in Technology, Education, and Science Act,” 110th Congress, May 10, 2007, https://www.congress.gov/bill/110th-congress/house-bill/2272

“ARPA-E: The First Seven Years,” ARPA-E, May 17, 2016, https://arpa-e.energy.gov/sites/default/files/Volume%201_ARPA-E_ImpactSheetCompilation_FINAL.pdf

“Program Directors,” ARPA-E, 2022, https://arpa-e.energy.gov/about/team-directory/program-directors?page=1

“An Assessment of ARPA-E,” National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017, .https://nap.nationalacademies.org/read/24811/chapter/2

Dominik P. Jankowski, “Russia and the Technological Race in an Era of Great Power Competition,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, September 2021, https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/210914_Jankowski_URMT2021.pdf?FCiMUQFzXJJJ8_NYJgOlYC8sIf8Rqh_Z

Dmitry Adamsky, “Defense Innovation in Russia: The Current State and Prospects for Revival,” Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation, January, 2014, https://escholarship.org/content/qt0s99052x/qt0s99052x_noSplash_c6bb01c7155b377e87104c036b7af828.pdf?t=nkzueo

“Moonshot Research and Development Program,” Cabinet Office of Japan, 2022, https://www8.cao.go.jp/cstp/english/moonshot1.pdf

According to a presentation by DARPA’s Defense Sciences Office (DSO). See here: https://www.darpa.mil/attachments/DiscoverDSODayPresentations_no_video.pdf

According to a presentation by DARPA’s Defense Sciences Office (DSO). See here: https://www.darpa.mil/attachments/DiscoverDSODayPresentations_no_video.pdf

David Adler, “Inside Operation Warp Speed: A New Model for Industrial Policy,” American Affairs, Summer 2021, Volume V, Number 2, https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2021/05/inside-operation-warp-speed-a-new-model-for-industrial-policy/

See here: https://www.ai.mil/