The PLA Has Transformed Itself To Take Taiwan

Motivated by the prospect of invading Taiwan, China’s military has greatly modernized and reformed. Whether or not an invasion of Taiwan is ever carried out, a new balance of power has been forged.

At the turn of the millennium, the People’s Liberation Army of China (PLA) was clearly far weaker than the United States Armed Forces. It was not even a serious threat to Taiwan, which possessed a better-trained military equipped with vastly more sophisticated weaponry. The PLA’s Ground Force was the largest in the world, but was armed with outdated Soviet-era equipment and entirely lacked professional, small-unit leadership. The PLA Navy was small and weak and its Air Force lagged at least a generation of fighter jets behind its Western peers.1 Japanese and U.S. defense planners could rest easy knowing that a US-aligned Taiwan acted as a buffer, protecting Japan’s maritime lines of communication while severely limiting the PLA Navy’s access to the Ryukyu Islands and the U.S. base at Okinawa. Following the “One-China principle,” the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has sought to bring Taiwan under its control ever since the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949 and the establishment of Taiwan—officially, the Republic of China—as a separate state. To the CCP, Taiwan is not just a barrier to its economic and military interests in the wider Pacific region, but also a direct challenge to its legitimacy. Until very recently, however, the prospect of China achieving what PLA documents call its “main strategic direction” seemed remote.2

You can listen to this Brief in full with the audio player below:

Just over twenty years later, everything has changed. The U.S. military’s ability to fight a war against a peer foe suffered from the extended wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, as budgets were spent to equip the Army for counterinsurgency warfare, rather than for a more conventional war against a professional military. The Navy and Air Force, in particular, suffered from years of neglect. Shipbuilding programs were scaled back and the reserve fleet cut,3 while the production run of the F-22 Raptor, then the world’s most advanced fighter jet, was drastically reduced.4 The demand for spending cuts in the wake of the 2007-09 Great Recession only exacerbated this situation. In contrast, the PLA has used the last two decades of China’s strong economic growth and lack of major military commitments to embark on a transformational military modernization. It has now achieved technological parity with the U.S. across many key domains while surpassing it in others, something almost unimaginable just two decades ago.

Taiwan, meanwhile, is trapped in a political quagmire. Until 1987, Taiwan was ruled as a military dictatorship under the nationalist Kuomintang party. The dictatorship pressed its claim to being the legitimate government of both Taiwan and mainland China, while also suppressing domestic attempts to formally declare Taiwan an independent country from the rest of China. Today, the Taiwanese government is led by the Democratic Progressive Party. The party favors Taiwanese independence, but is staffed with cadres of civil society activists and lawyers who do not understand their own military—for so long aligned with the Kuomintang, now the opposition party—and have only a weak interest in reform.5 Meanwhile, institutional inertia and intra-military competitions for prestige bias Taiwanese military procurement towards high-prestige, expensive weapons systems bought under the U.S. Foreign Military Sales program, such as F-16 fighter jets and Abrams tanks.6 Given the PLA’s projected aerial dominance in the first phase of an invasion of Taiwan, these are likely to be of little use.7 Taiwan’s citizens have yet to realize the seriousness of the situation, while the political elite finds it more convenient to let them rest under the comforting yet unjustified assumption that the U.S. military still retains its ability to defend Taiwan with relative ease.

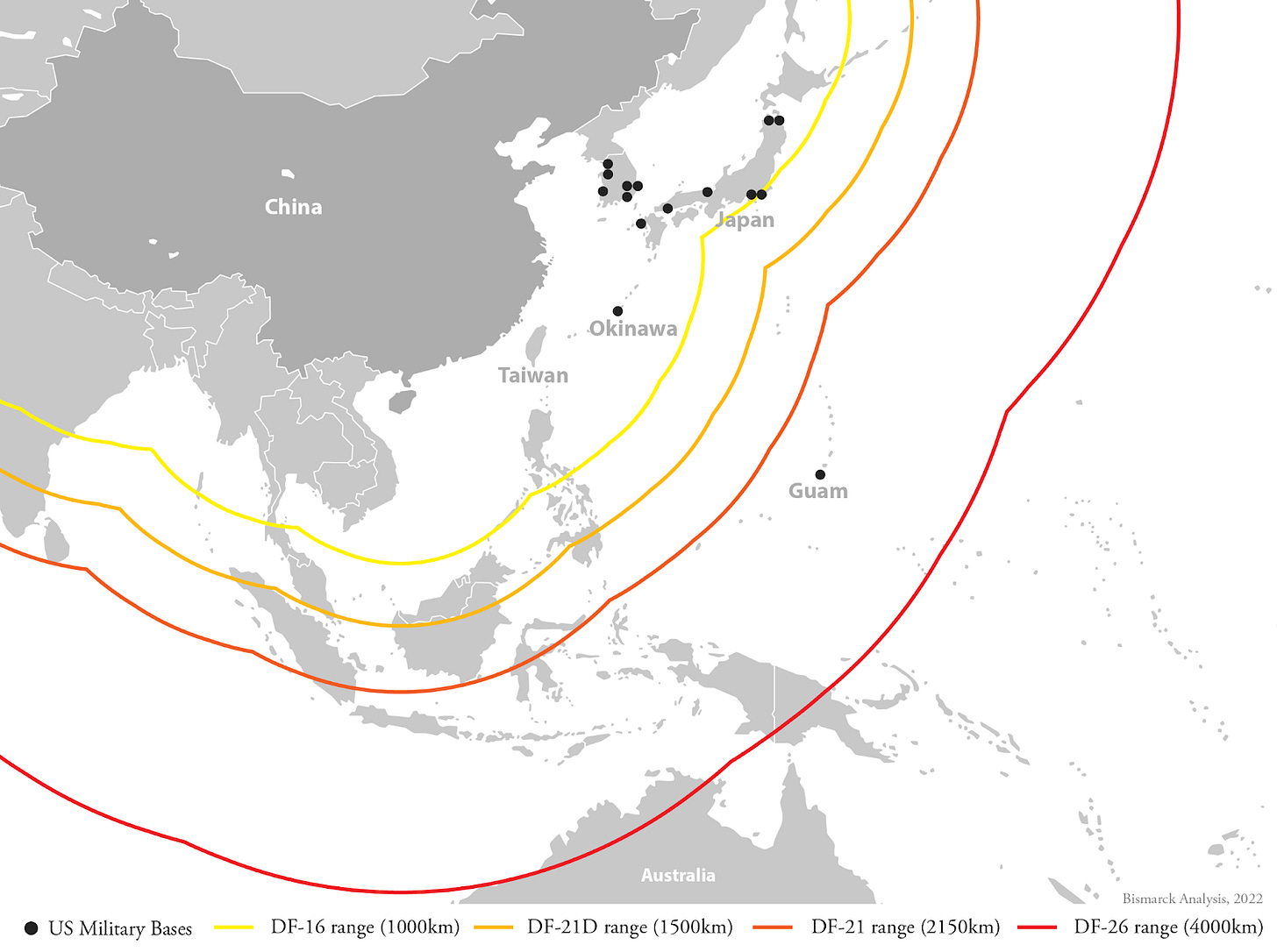

The result is a uniquely pivotal moment for the balance of power in East Asia. The PLA now qualitatively matches the Taiwanese military, while retaining its traditional vast advantage in size. Most importantly, it has specialized in the development of long- and medium-range ballistic missiles, becoming the world leader in this vital domain. The ability of the United States to offer meaningful military assistance to Taiwan is now in serious doubt. Taiwanese airfields, Japanese airfields, and the US’s own aircraft carriers are now vulnerable to China’s precision strike forces. America’s enduring advantage in airpower is greatly reduced if its planes get easily destroyed on the ground or are denied the option of aerial refueling. Despite Taiwan’s natural geographical advantages, and despite many aspects of modern warfare favoring the defender, the island appears suddenly vulnerable.8

Whether successful or not, an invasion of Taiwan would have far-reaching consequences around the globe. China and Taiwan are two of the world’s largest and most important manufacturing economies, so the immediate economic disruption would be tremendous, to say nothing of potential long-term disruption due to strained relations with the US, Japan, and other major economies. A successful invasion of Taiwan would signal the definitive end of already shaky hopes that economic growth would lead to political liberalization in China. The CCP would acquire a tremendous new source of domestic political legitimacy, not from economic growth, but from military intervention, that might become tempting to refresh. The PLA Navy would gain new access points to the Pacific9 and, per PLA documents, create a credible threat of blockading Japan entirely, should the need arise.10 U.S. security commitments both in East Asia and worldwide would come into serious doubt, putting unprecedented pressure on the US’ global standing. Conversely, a failed invasion would be disastrous for China’s domestic political stability. In the words of Xi Jinping, if the CCP cannot deal with Taiwanese independence, “we will be overthrown.”11

Despite the PLA’s transformation, an invasion would still be an enormous undertaking. It may never happen. Importantly, the Chinese government has other options available to try to cow Taiwan into submission.12 Yet, the PLA’s successful modernization has dramatically widened the spectrum of military options available to China’s political leaders and reforged the balance of power in East Asia.13 Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the modernization effort, however, has not been technological, but doctrinal. Quietly, the PLA has completely overhauled the way it approaches warfare right down to the level of individual units. Once famed for its hierarchical culture and institutional inflexibility, the Chinese military now officially approaches war with the mindset that the autonomy and decision-making skills of its junior officers are what will ultimately prove decisive. This doctrinal overhaul is not necessarily a live or ubiquitous tradition at the level of the rank-and-file yet. That the PLA should be prepared to countenance such a radical departure from its traditional mindset, however, is still remarkably underappreciated in the West. More than anything else, it is a deep marker of the PLA’s institutional seriousness, and illustrates the depth of their commitment to building a force capable of taking Taiwan.

Slaughter on the Beaches

The largest amphibious assault in history occurred during the Normandy landings of the Second World War, when the Allies successfully established a beachhead in northern France against German opposition. While military technology has changed profoundly in the 80 years since, many geographic and logistical constraints of amphibious operations remain the same. In the context of the island of Taiwan, however, the comparison is misleading. An invasion of Taiwan would be a vastly more challenging operation than D-Day. In Normandy, the Allies had overwhelming air superiority against a German air force that was already largely defeated. They had complete command of the sea, under no threat from German submarines. For landing troops, there were a plethora of suitable beaches to choose from, many weakly defended. In any case, the best German units were mostly far away on the Eastern Front. A wildly successful deception campaign, Operation Fortitude, trapped the Germans’ reserve force in the area of Pas de Calais, where the German High Command had become convinced that the main invasion was yet to occur.14 Even so, the lightly-armed German units still gave the American troops on Omaha Beach a hellish battle on the first day. Afterwards, the Normandy campaign devolved into a gruelling war of attrition until the encirclement at Falaise, over two months after D-Day.

The PLA would benefit from none of these advantages in an invasion of Taiwan. There are only a handful of suitable beaches to choose from, no more than fourteen.15 The remainder are either too small to accept landing craft of any real size, or are surrounded by mountainous terrain that massively advantages the defending force. The Taiwanese military would know in advance with a high degree of certainty where they will land and would be able to concentrate troops accordingly. In the modern age of satellite technology, the invasion force cannot be hidden; everyone with an internet connection would be able to see the PLA’s preparations.16 Moreover, the weather in the Taiwan Strait that separates the island from mainland China is usually so bad that there are only a few weeks of the year suitable for large-scale amphibious operations—the months of April and October.17 Unless an unusually wide window of good weather opened at some other time of year, China could not credibly threaten an invasion beyond these eight weeks, ruling out any strategy of trying to wear down Taiwan by compelling its defenses to stay at a perpetual level of high readiness. While China could probably establish a significant degree of air superiority, the Taiwanese Air Force is well prepared to survive an opening missile barrage, with hangars buried deep in mountains and highly-trained runway repair crews.18 Most importantly, Taiwan has no other threat to worry about; the PLA will have to face the entirety of whatever force Taiwan can muster.

The PLA’s problems would not end there. Cheap precision-guided anti-ship missiles have proliferated across the world, and Taiwan has been a major customer. Relatively lightly-equipped troops can inflict huge casualties on an attacking force’s landing craft before it even makes it to the shore.19 Moreover, all this assumes that the PLA would have to defeat only the armed forces of Taiwan. If the United States and Japan entered the fight in a meaningful capacity, China’s odds of victory would decrease even further. Therefore, any war plan for invading Taiwan must find a way to keep its allies out of the theater of war at least until the landing force is well established ashore.20

Consequently, despite the PLA’s overwhelming numerical advantage, it would face enormous challenges if ordered to invade Taiwan. A successful conquest would be the greatest achievement of any modern military force since the Second World War. The PLA’s leaders have always been acutely aware of the difficulty of the task ahead of them, especially since the 1996 Taiwan Strait Crisis, when the U.S. granted Taiwanese then-President Lee Teng-Hui a visa for a visit to Cornell University, provoking Chinese missile tests and amphibious assault exercises. The arrival of two U.S. carrier battle groups in the Strait forced the Chinese political elite to back down in the face of the stark reality that they had no answer to America’s military might. Ever since then, the pace of Chinese military reform and build-up has accelerated, with the pace picking up still further since the ascendance of Xi Jinping in 2012.

The PLA’s Ideological Transformation

The PLA is perhaps the world’s most politicized military. It does not officially serve the Chinese state, but functions formally as the armed wing of the CCP. Its operational theories were historically tightly linked to party doctrine and the writings of Karl Marx and Chairman Mao. The latter’s theory of “People’s War” underpins PLA operational thinking today, even though Mao wrote from the perspective of commanding an armed insurgency against a qualitatively superior foe. The PLA today is in a very different position, but still leans on Mao’s understanding of the importance of superior mass, high-tempo maneuver, political will, deception operations, and small-unit infiltration techniques.21 Similarly, its traditional focus on the land domain, relative neglect of the sea, and continued use of conscription all stem from Mao’s own preoccupations and an era where large-scale, conventional, lengthy wars between great powers still seemed imminent. Even today, former PLA Ground Force generals are still greatly over-represented in the uppermost ranks of the PLA’s command echelon relative to PLA Navy or PLA Air Force commanders, a lingering legacy of Maoist theory.22

Beginning in the 1980s, however, PLA theorists realized that technological developments and China’s growing ability to harness them meant that an unchanged Maoist framework could no longer serve as the basis for operational theory. Deng Xiaoping came to stress a maritime understanding of the Maoist concept of “active defense,” evolving PLA thinking away from Mao’s land-centric conception of warfare. Rather than defend in-depth on land, trading territory in exchange for time and blood, China would expand its borders into the oceans, away from its coastal, fast-growing cities. Furthermore, the presence of nuclear weapons and the purposefully peaceful trajectory of China’s rise had dramatically reduced the likelihood of all-out war between great powers, and Deng shaped the PLA accordingly, to prepare for local, limited wars, fought by smaller, professional forces with modern equipment. Over time, Deng’s contributions came to underpin China’s vast naval buildup and the Chinese Army’s slow, relative loss of prestige and manpower vis-à-vis the Navy and Air Force, a trend that has accelerated under Xi Jinping.23

In line with this development of doctrine, Mao’s concepts came to be known by adapted names. “People’s War” became “People’s War under Modern Conditions,” which in turn by 2004 evolved into “People’s War in Conditions of Informationization.” The equivalent Western jargon is “network-centric warfare,” which essentially describes the integration of advanced communications technology into the conduct of warfare, enabling faster and greater information sharing between different elements of a military force. The Chinese military, however, adopted “network-centric warfare” as a guiding operational concept far in advance of their capacity to put it into practice, and have proceeded to shape their force accordingly over the last two decades.

The preoccupation with technological modernization and naval dominance in China’s near vicinity are, of course, both transparently relevant to the question of a campaign for Taiwan. From PLA documents, it is possible to track the conceptual shift from a conscript army designed to fight brutal wars of attrition against technologically superior foes in land-based conflicts such as the Korean War, to a modernized, technologically sophisticated, semi-professional force that focuses on naval power projection. In the PLA’s own thinking, however, this represents doctrinal evolution, not revolution, and the process of modernization has come with no loss of ideological purity. Under Xi, military theorists foresee a new era of “People’s War in Intelligentized Conditions,” where China’s leadership in artificial intelligence and robotics is brought to bear in warfare, but still in a fashion consistent with Mao’s original framework.

The Rocket Force

Since 2016, the PLA Rocket Force has operated as a stand-alone service, a fourth branch of the military equal in status to the Ground Force, Navy, and Air Force. Once a small, nuclear-oriented force, the former Second Artillery Corps’s rise to such prominence reflects China’s best-in-class, land-based ballistic and cruise missile capability. Notably, it was a strange quirk of Cold War arms control that allowed the PLA to race far ahead of the other great powers in this domain. The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, signed in 1987 between the United States and the Soviet Union, banned the deployment of all ballistic and cruise missiles with a range from 500km to 5500km, thus effectively locking both the U.S. and Russia out of an entire generation’s worth of mid-range rocket development.24 China, however, was not a signatory. While the Trump Administration finally pulled the U.S. out of the INF treaty in 2019, the U.S. today possesses virtually no land-based mid-range ballistic missiles at all, a gap it is scrambling to fill.25

The PLA’s growing missile arsenal now threatens not just the Taiwanese mainland, which is little more than 100 miles from the Chinese coast, but Japan and South Korea as well.26 The DF-21C, brought into service in 2008, was the PLA’s first mid-range ballistic missile with a range (c. 2000km) long enough to threaten the US’s major Pacific base at Yokosuka in Japan, which hosts a permanently forward-deployed aircraft carrier and supports the Seventh Fleet—the largest U.S. Pacific Fleet. The carrier itself, even when at sea, is plausibly threatened by the DF-21D anti-ship variant, though China has yet to conclusively demonstrate its ability to hit a moving target defended by escorts and employing active countermeasures at sea. Even the U.S. base at Guam now lies in range of the DF-26, brought into service in 2018 and boasting a range of c. 5000km. It too has an anti-ship variant, although once again little is known about its true capabilities, and other assets would be required to locate any aircraft carrier the U.S. might have near Guam or in the Indian Ocean, before firing the missile.

The military significance of China’s missile dominance is hard to overstate. Road-mobile launchers make it difficult for the U.S. to destroy much of the Chinese arsenal on the ground, even in the event that the U.S. does rebuild its own intermediate-range missile arsenal and places launchers in the Pacific to threaten the Chinese mainland. The threat to its aircraft carriers should compel the U.S. to invest enormous resources in missile defense. While shipboard lasers, directed energy weapons, and projectiles launched from electromagnetic railguns are all theoretically plausible options that may enable carrier battle groups to stay relevant, lasers and directed energy weapons powerful enough to deal with incoming missiles come with extremely high energy requirements, far beyond what the power systems of today’s frigates and destroyers can provide.27 Interceptor missiles such as the SM-6 are the best solution to the ballistic missile threat available today, but come at an agonizingly high unit cost (nearly $5 million per missile).

Even assuming that the U.S. can at least partially solve these problems, the inevitable conclusion is that China has leveraged its missile buildup to transform its proximity to Taiwan into a vast strategic advantage. U.S. airpower, the hegemon’s most powerful military asset, will struggle to exert much influence when a war for Taiwan begins. When the PLA’s build-up is initially detected, the U.S. will probably be forced to move many of its most vital naval and airborne assets further away from Taiwan or else risk losing them in the first hours of war. The U.S. will then confront the formidable task of breaking down the key systems underpinning China’s strike complex so as to allow its forces to compete directly in the fight over Taiwan itself. Between the sheer range of China’s rocket force, the limited reach of modern stealth fighter jets such as the F-35 and F-22 Raptor, and the inherent vulnerability of aerial refueling tankers and airborne early warning and control systems, this task will likely take at least several weeks.28 The PLA’s objective is to ensure that, by then, the decisive phase of the war will be over. To achieve that goal, the contributions of the Air Force, Navy, and Ground Force will be decisive.

The Air Force

Throughout a war for Taiwan, the PLA Air Force (PLAAF) and its assets will play a vital role. In the first hours of the war, its fighter jets and bombers must follow up on the Rocket Force’s opening salvo to degrade the Taiwanese Air Force, destroying as many jets in the air as possible while continuing to target ground infrastructure—especially runways—to lower Taiwan’s sortie rate.29 To this end, China has spent the last twenty years building a modern air force almost from scratch, aided by industrial-scale espionage that has allowed the PLAAF to build the J-20 Dragon, the world’s only plausible direct competitor to the F-22 and F-35, in the fifth-generation stealth fighter category.30 Build quality and engine outputs—serious flaws in the early batches of J-20s—have substantially improved as the program has progressed. Taiwan possesses a sophisticated integrated air defense system of its own, and to establish full aerial superiority over the Taiwan Strait, suppression and destruction of that system will be essential. The relatively small but fast-growing PLAAF stealth fighter fleet will play a key role in accomplishing this objective.

To maintain aerial dominance, China’s own integrated air defense system—one of the domains where China is a world-leader at least equal to the United States—will be essential.31 China’s long-term strategic partnership with Russia has come with enormous payoffs. It has enabled China to buy best-in-class Russian surface-to-air missile systems such as the S-400 directly and enabled China to build their own surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) that both incorporate the best Russian technologies and domestically developed components which surpass Russian technology—notably their radars.32 Even though Taiwan’s air defenses may well be able to inflict substantial damage on the PLAAF’s fighter jet fleet, and the USAF still enjoys substantial jet-for-jet technological advantages, it will be extremely challenging for the U.S. Air Force to operate over the Taiwan Strait. Once again, Chinese strategy has taken its natural geographic advantages and maximized them through key strategic investments.

The Navy

The PLA Navy (PLAN) has a vital twofold role in enabling China’s victory over Taiwan. First, it must contribute to the effort to keep the U.S. military out of the immediate fight for the island, for as long as it possibly can. Second and most importantly, it must land the Ground Force on the beaches. Neither would be easy, but the PLAN has been the beneficiary of enormous increases in funding and capability over the last two decades that make its ability to achieve both goals at least somewhat plausible today. Now the largest navy in the world by number of ships, it threatens American seapower not just through ballistic missiles launched from the mainland, but also through its large and ever-more sophisticated attack submarine fleet. Currently, it operates a fleet of about 42 reasonably modernized diesel-powered submarines, and six modernized nuclear attack submarines (the Shang-class). The U.S. Navy submarine fleet, in contrast, is all-nuclear.

While diesel-powered submarines lack the range, speed, and endurance of nuclear submarines, this hardly matters for a fight in the seas near the Chinese mainland. Moreover, modernized diesel-powered submarines with air-independent propulsion systems (such as China’s Yuan-class) are actually quieter and harder to detect than nuclear-powered craft, since nuclear reactors require constantly recirculating water to keep them cool. Diesel-powered submarines, in contrast, are smaller and stealthier. They are ideally adapted to shallow waters near coastlines and are able to go completely dark on the seafloor before firing at passing vessels.33 As far back as 2006, a Chinese submarine—of an old, unsophisticated design—surfaced in the middle of a U.S. carrier group, hitherto completely undetected by the carrier’s escorts.34 Outside of the comforting confines of a scripted exercise, anti-submarine warfare is incredibly hard.

In the event that Taiwan or the U.S. do manage to contest the skies, the PLAN here too has a key role to play, as part of China’s multilayered air defense system. Under Xi, the rate of shipbuilding across the board has ramped up dramatically, but the increase in China’s capacity to build large surface vessels has been truly extraordinary. In recent times its yards have produced about two to three new surface combatants for every one new U.S. Navy vessel.35 In 2013, China had no modern destroyers at all. Now, 18 Type 052D vessels are in service,36 while the hefty Type 055 (Renhai-class) cruisers combine anti-air, anti-submarine, anti-ship, and land-attack capabilities into one vessel. In wartime, Western military theorists expect at least some of these to sail east of Taiwan to battle with Western aircraft, while others could sail throughout the wider Pacific—or even perhaps the Atlantic—to draw U.S. resources away from Taiwan.

While the expected loss rate of Chinese surface vessels in this kind of scenario is no doubt very high, the fact that there is more shipbuilding capacity in Shanghai alone than in the entire United States might make the PLA far more willing to lose ships than any Western force.37 The output of Chinese yards now makes up a little under half of the world’s shipbuilding volume by tonnage, having just overtaken South Korea, while the U.S. has just one major civilian yard remaining that produces large vessels, General Dynamics NASSCO at San Diego.38 China’s planned tight integration between military and civilian yards has enabled the creation of a large reservoir of shipbuilding skills,39 a strategy overseen by Xi Jinping personally, who chairs a commission for advancing the integration of civilian and military technologies.40 In the U.S., however, the specialization of military yards and the inconsistent flow of work from the Pentagon has slowly degraded the quantity and quality of the workforce.41 The PLA Navy has expanded so fast largely because it can order different ships in the same class from a variety of yards, an option not available to Western defense planners who are now largely confined to ordering the entirety of a given class of ship from the one yard available to produce it.

This reservoir of civilian vessels would prove a valuable asset in any PLA invasion of Taiwan. It was, at one point, common to argue that the PLA’s lack of specialized amphibious transport capacity meant there were no serious Chinese plans to invade the island. This took for granted the U.S. military’s tendency to opt for excessively high-tech solutions and misapplied it to the PLAN. The majority of the landing craft are likely to be civilian-standard “roll-on/roll-off” (RORO) ferries, used in peacetime for car transport. Since the 2016 National Defense Transportation Law, Chinese shipyards are required to build this kind of craft with potential military use in mind. As of 2020, the PLAN has begun exercising amphibious landings incorporating civilian RORO ferries,42 the clearest indication yet that, contrary to the U.S. Defense Department’s analyses, they will not let their military landing craft shortage hold them back from Taiwan’s beaches.

The Ground Force

Even if the combined efforts of the Rocket Force, Air Force, and Navy succeed in landing a substantial force on Taiwan’s beaches, the burden of winning the war will fall primarily on the heavy armor of the Ground Force, barring a sudden Taiwanese surrender. Of all the branches of the Chinese military, the PLA’s Ground Force is on the longest journey of transformation. Once a conscription-based force that sought to compensate for technological deficiencies with tactical ingenuity and sheer mass, it has been relentlessly shrinking in size since 1985. At that time, it was a force of 4 million, largely equipped with outdated Soviet equipment based on 1950s designs and operating under outdated Maoist doctrine. Now the total size of the Ground Force numbers just under one million and, while some technological deficiencies in equipment remain, the Ground Forces under Xi are aggressively pursuing a decentralized vision of combined arms warfare that—perhaps surprisingly—demands high levels of risk-taking and autonomy from junior officers.43 Whereas in the Cold War it was the West that looked askance at sluggish communist military bureaucracies, regarding them as a key weakness ripe for exploitation, increasingly the situation has reversed.

While it is commonly stated that the PLA Ground Force structural reforms are modeled on the U.S. Army’s Brigade Combat Teams, in reality they owe far more to the post-2007 Russian military reform, which should be unsurprising given the close historic and ongoing Sino-Russian military cooperation. Russia’s experiences in Chechnya and Georgia showcased a sluggish command structure unable to react swiftly to changing realities on the battlefield, and crippled by lack of high-quality intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) assets, a legacy of the Soviet-era military.44 The solution, in part, was to break up divisions and push more logistical support and firepower down to smaller, independent brigades, a model closely followed by the Chinese military reforms.45 The sheer density of artillery is another key concordance between Russian and Chinese ground forces. Both pack almost as many artillery pieces in single brigades—units of just 4000-5000 soldiers—as some European countries, such as the United Kingdom, operate across their entire ground force.46 While much of this artillery is not on the technological cutting-edge, the widespread introduction of cheap reconnaissance drones across Chinese brigades should enable substantial improvements in accuracy, as both Russia and Turkey have demonstrated on the battlefield in Ukraine and Syria.47

The great weakness of the PLA Ground Force, however, remains its lack of combat experience. Nothing can compensate for experience under fire, especially at the level of junior leadership. Prior to the late 1990s, the PLA entirely lacked a professional non-commissioned officer (NCO) corps, and while it has slowly shifted roles such as tank commanders and specialized squad leaders away from final-year conscripts to NCOs, the NCO remains a new role with an uncertain cultural status.48 The relationships between officers, NCOs, and enlisted men remain more problematic than in Western militaries.49 Senior leadership is well aware of the issue and has spoken publicly, with surprising frankness, about the costs of China’s long peace.50 Though training is now conducted with far greater realism than was customary in prior decades, it still remains an inadequate substitute for the reality of combat. Moreover, while China’s doctrinal system places ever more responsibility on the shoulders of junior leaders, it remains unclear whether the culture and systems to enable them to handle this responsibility in combat are truly live.

Will Taiwan Fight?

The ancient military theorist Sun Tzu, author of The Art of War, has become extremely popular in the West today, but also exerts an extraordinary degree of influence over the PLA. Senior commanders can quote lengthy passages from memory, while his work is apparently a mandatory textbook to be read by enlisted men and officers alike.51 While the Chinese government would certainly prefer a bloodless takeover of Taiwan to the costs and risks of a military invasion, Sun Tzu’s vision of “winning without fighting” surely also holds great appeal for the PLA, given the inherent difficulties of the campaign and their troops’ lack of combat experience. The temptation must be enormous to give Taiwan the opportunity to surrender, perhaps after the seizure of Kinmen, the Matsu Islands, and most of all the Penghu Islands, which sit just 50km from the coast of Taiwan, but are relatively lightly defended.52 Or perhaps the PLA will seek to impose a naval blockade while suggesting that Taiwan begin the political process of a surrender that saves face.53

The odds of Chinese victory through coercion and propaganda are better than they might appear. Polling reveals that 65% of Taiwanese have no confidence their country can be defended.54 The Taiwanese military and political leadership seem to believe that if war comes, the island can only be held for two weeks if the PLA are not stopped on the beaches.55 Morale in the Taiwanese Army is notoriously low and its training of conscripts and reservists is often ridiculed, though affairs are much better in the Air Force. The men and women of Taiwan are most likely not prepared psychologically for what it would take to deter the PLA. Taiwan would have better odds of preserving its independence were its people trained and prepared to fight a brutal campaign, street by street, in the bombed-out rubble of Taipei—followed by years of vicious insurgencies. Faced with the choice between a plunge into guerilla warfare or the choice of following in the footsteps of Hong Kong—once a largely autonomous city but now increasingly under direct control from Beijing—it appears all too plausible that Taiwan’s citizens will choose the latter.

As the PLA ramps up its preparations for war, the strategic context at the start of 2022 consists of a series of paradoxes. China has built a vast, modern, innovative military force, in the erstwhile hope it will never be used to its fullest potential. The PLA’s propaganda and myth-making partly undermine its own combat effectiveness, but may also constitute its best hope of taking Taiwan. The United States military, for its part, must engage in extensive preparation for war via forward deployment of key assets and painstaking reshaping of its own forces, on the assumption it will be ordered to fight for Taiwan. Yet the best hope for Taiwan’s defense may well lie in the U.S. making it very clear to Taiwanese policymakers that they cannot assume any help will be coming at all—at this point, it seems as though nothing else will break the island’s political paralysis and finally force it to take its defense seriously. Politically popular but militarily useless purchases of expensive American tanks and fighter jets will inexorably contribute to a Taiwanese defeat. In one final paradox, it is the PLA’s own success in finding a way to negate a technologically superior power—the United States—that so clearly constitutes a perfect doctrinal model for Taiwan to follow. The contemporary Chinese Communist Party, however, appears to be consistently more doctrinally flexible and innovative than the liberal democracies that it confronts.

For a particular scathing assessment of the PLA’s capabilities around this time, see Bates Gill & Michael E. Hanlon, “China’s Hollow Military”, Brookings Institute, June 1, 1999, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/chinas-hollow-military/

This term, referring to the conquest of Taiwan, is used extensively in The Science of Military Strategy (2013) a core PLA text for officers across the force, written by the Academy of Military Sciences. An English translation is available at https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/CASI/documents/Translations/2021-02-08%20Chinese%20Military%20Thoughts-%20In%20their%20own%20words%20Science%20of%20Military%20Strategy%202013.pdf?ver=NxAWg4BPw_NylEjxaha8Aw%3d%3d

Robert C. O’Brien, “The Navy’s Hidden Crisis”, Politico, February 5, 2015, https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/02/navy-hidden-crisis-114943/

Kris Oborn, “F-22 Raptor: Why Did the U.S. Military Cut Back the Ultimate Fighter?”, National Interest, August 1, 2021, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/f-22-raptor-why-did-us-military-cut-back-ultimate-fighter-190892

Tanner Greer, “Why I Fear for Taiwan”, Scholars Stage, 11 September, 2020, https://scholars-stage.org/why-i-fear-for-taiwan/

Tanner Greer, “Taiwan’s Defence Strategy Doesn’t Make Military Sense”, Foreign Policy, Sept 17, 2019, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/taiwan/2019-09-17/taiwans-defense-strategy-doesnt-make-military-sense

Colin Carroll & Rebecca Lissner, “Forget The Subs: What Taipei Can Learn from Tehran About Asymmetric Defense”, War on The Rocks, April 6, 2017, https://warontherocks.com/2017/04/forget-the-subs-what-taipei-can-learn-from-tehran-about-asymmetric-defense/

For an excellent assessment of the current cross-Strait military balance, see Michael Hunzeker & Alexander Lanoszka, “A Question of Time: Enhancing Taiwan’s Conventional Deterrence Posture”, Center for Policy and Security Studies, November 2018, http://csps.gmu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/A-Question-of-Time.pdf

Tanner Greer, “Losing Taiwan Means Losing Japan”, Scholars Stage, February 26, 2020, https://scholars-stage.org/losing-taiwan-means-losing-japan/

From Yang Pushuang (ed), 2013. “The Japanese Air Self Defence Force”, Air Force Command College, Beijing, pp.190-191, the following remarkable quote: “As soon as Taiwan is reunified with Mainland China, Japan’s maritime lines of communication will fall completely within the striking ranges of China’s fighters and bombers…Our analysis shows that, by using blockades, if we can reduce Japan’s raw imports by 15-20%, it will be a heavy blow to Japan’s economy. After imports have been reduced by 30%, Japan’s economic activity and war-making potential will be basically destroyed. After imports have been reduced by 50%, even if they use rationing to limit consumption, Japan’s national economy and war-making potential will collapse entirely…blockades can cause sea shipments to decrease and can even create a famine within the Japanese islands” (quoted in Ian Easton, (2017) “The Chinese Invasion Threat: Taiwan’s Defense and American Strategy in Asia”, Eastbridge Books.)

Annette Lu, “The DPP faces historic challenge,” Taipei Times, November 14, 2016, https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/editorials/archives/2016/11/14/2003659209

Some of these scenarios are outlined in David Lague & Maryanne Murray, “T-Day: The Battle for Taiwan”, Reuters Investigates, November 5, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/taiwan-china-wargames/

PLA strategy documents frequently discuss options for aggression against Taiwan short of all-out invasion, especially a blockade designed to force the island into submission. See, for example: Zhang Yuliang (ed.), The Science of Campaigns, National Defense University Press, 2006. An English-language translation is available at https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/CASI/documents/Translations/2020-12-02%20In%20Their%20Own%20Words-%20Science%20of%20Campaigns%20(2006).pdf

For a discussion of Operation Fortitude, see Ernst S. Tavares (2001), “Operation Fortitude: The Closed Loop D-Day Deception Plan”, U.S. Air Command and Staff College, https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/pais/people/aldrich/vigilant/tavares_fortitude.pdf

Ian Easton, “Hostile Harbors: Taiwan’s Ports and PLA Invasion Plans”, Project 2049, July 22, 2021, https://project2049.net/2021/07/22/hostile-harbors-taiwans-ports-and-pla-invasion-plans/

Note how quickly the recent Russian military buildup near Ukraine was detected, and how accurately its scale has been assessed. Firms such as Maxar Technologies have used their commercial satellites to supply the world’s media with high-resolution images of the movements of battalion tactical groups. The Chinese build-up for a Taiwan invasion would be of vastly greater scale, requiring movements of millions of men and vast quantities of materiel. Commodities markets would show obvious distortions as China began stockpiling oil, gas, wheat, and metals. No matter how hard the PLA tries to conceal these preparations, it defies credulity to think that it would have any kind of surprise factor working in its favor. This question is discussed more extensively in Ian Easton, (2017) “The Chinese Invasion Threat: Taiwan’s Defense and American Strategy in Asia”, Eastbridge Books.

Tanner Greer, “Taiwan Can Win a War with China”, Foreign Policy, September 25, 2018, https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/09/25/taiwan-can-win-a-war-with-china/

In 2014, Taiwanese sappers lowered the world record for fastest runway repair to three hours, down from the four-hour record previously held by an Israeli team. See Joseph Yeh, “Air Force Drill Displays Rapid Runway Repair Skill”, The China Post, January 14, 2014, https://chinapost.nownews.com/20140114-79542; Ian Easton, “Taiwan, Asia’s Secret Air Power, The Diplomat, September 25, 2014, https://thediplomat.com/2014/09/taiwan-asias-secret-air-power/

Michael Beckley, (2017). “The Emerging Military Balance in East Asia: How China’s Neighbours Can Check Chinese Naval Expansion”, International Security Vol. 42 (2), pp.78-119, https://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/files/publication/ISEC_a_00294-Beckley_proof3.pdf

In the Western literature, this vision of war has become known as an “anti-access/area denial” strategy, often shortened to A2/AD. This term is not found in the Chinese military literature, which instead uses the term “counter-intervention”, and is misleading in some important ways. Most notably, the Chinese strategy is not to entirely deny the seas and skies around Taiwan to the U.S. military, but to try to delay the entry of a sizable U.S. force that can substantially affect the course of the war. Moreover, the phrase “area denial” conjures up visions of primarily defensive Chinese strategy vs U.S. forces: in reality, PLA planners aim to proactively destroy whatever high-value U.S. assets that are in striking distance within the first few hours of a war. This issue is discussed extensively in Timothy Heath & Andrew Erickson (2015) “Is China Pursuing Counter-Intervention”, Washington Quarterly, Vol 38: 3 pp.143-156, https://www.andrewerickson.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Counter-Intervention-Regional-Restructuring_China_TWQ_2015-Fall_Heath-Erickson.pdf

Headquarters, Department of the Army (2020). “Chinese Tactics”, Army Techniques Publication, No.7, http://www.andrewerickson.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Army_Doctrine_Chinese-Tactics_20210809.pdf

Dennis J. Blasko, “Walk, Don’t Run: Chinese Military Reforms in 2017”, War on the Rocks, Jan 9th, 2017, https://warontherocks.com/2017/01/walk-dont-run-chinese-military-reforms-in-2017/

The theoretical evolution of PLA doctrine is discussed more extensively in

Edmund Burke., Kristen Gunness, Cortez A. Cooper III, and Mark Cozad, (2020) “People's Liberation Army Operational Concepts.” RAND Corporation, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA394-1.html.

Jacob Stokes, “China’s Missile Program and U.S. Withdrawal from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty”, U.S-China Economic and Security Review Commission, February 4, 2019, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/China%20and%20INF_0.pdf

For an overview of the U.S Army’s efforts to catch up in this domain, see Andrew Feickert, “U.S. Army Long-Range Precision Fires: Background and Issues for Congress”, Congressional Research Service, March 16, 2021, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46721

David Lague & Benjamin Kang Lim, “New Missile Gap leaves U.S scrambling to counter China”, Reuters Investigates, April 25, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/china-army-rockets/

For a more extensive discussion of the energy requirements of these weapon systems, see Ronald O’Rourke, “Navy Shipboard Lasers for Surface, Air, and Missile Defense: Background and Issues for Congress”, Congressional Research Service, June 12, 2015, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/weapons/R41526.pdf

This dilemma has led at least one analyst to propose that the U.S. prepare to deploy an Army Corps on Taiwan in the event of the PLA signaling an invasion, since it would be a valuable asset for Taiwan’s defense and more far more resilient in the face of China’s opening rocket salvoes than fighter jets or surface ships. See Brian J. Dunn, “Drive Them Into the Sea”, English Military Review, September-October 2020, https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Portals/7/military-review/Archives/English/SO-20/Dunn-Drive-Into-Sea-1.pdf

This line of action is outlined in numerous PLA manuals (Informationized Joint Operations, in particular), discussed extensively in Ian Easton, (2017) “The Chinese Invasion Threat: Taiwan’s Defense and American Strategy in Asia”, Eastbridge Books.

Justin Bronk, “Russian and Chinese Combat Air Trends: Current Capabilities and Future Threat Outlook”, Royal United Services Institute Whitehall Papers, 30 October, 2020, https://static.rusi.org/russian_and_chinese_combat_air_trends_whr_final_web_version.pdf

Office of the Secretary of Defense (2020). “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China”. U.S. Department of Defense, https://media.defense.gov/2020/Sep/01/2002488689/-1/-1/1/2020-DOD-CHINA-MILITARY-POWER-REPORT-FINAL.PDF

Timothy R. Heath, “How China’s New Russian Air Defense System Could Change Asia”, War on The Rocks, January 21, 2016, https://warontherocks.com/2016/01/how-chinas-new-russian-air-defense-system-could-change-asia/; For an in-depth analysis of the development of China’s air defense network, see Justin Bronk, “Modern Russian and Chinese Integrated Air Defense Systems: The Nature of the Threat, Growth Trajectory and Western Options”, RUSI Occasional Papers, 15 January, 2020, https://static.rusi.org/20191118_iads_bronk_web_final.pdf

For an overview of the capabilities of diesel-electric submarines and the challenges they pose to the U.S. Navy’s all-nuclear submarine force, see Kevin Noonan, “The Navy Isn't Prepared To Face The Growing Diesel Submarine Threat”, The Drive, November 2, 2021, https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/42900/the-truth-about-the-growing-diesel-submarine-threat-from-a-veteran-sub-hunter

David Axe, “This Picture is a Naval Nightmare: A Submarine in Shooting Range of an Aircraft Carrier”, National Interest, July 3, 2018, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/picture-naval-nightmare-submarine-shooting-range-aircraft-carrier-24932

Andrew S. Erickson, “Chinese Naval Shipbuilding: Full Steam Ahead”, The Maritime Executive, January 18, 2019, https://www.maritime-executive.com/editorials/chinese-naval-shipbuilding-full-steam-ahead

Ronald O’Rourke, “China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress”, Congressional Research Service, December 2, 2021, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/RL33153.pdf

Daniel Caldwell, Joseph Freda, & Lyle Goldstein, (2020) “China Maritime Report No. 5: China's Dreadnought? The PLA Navy's Type 055 Cruiser and Its Implications for the Future Maritime Security Environment”, China Maritime Studies Institute, U.S. Naval War College, https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1004&context=cmsi-maritime-reports

Mark H. Busby, “Sealift and Mobility Requirements In Support of The National Defense Strategy”, statement before the Committee on Armed Services Subcommittee on Seapower and Projection Forces and Subcommittee on Readiness, March 11, 2020, https://www.transportation.gov/testimony/sealift-and-mobility-requirements-support-national-defense-strategy

Andrew S. Erickson, “China’s Naval Shipbuilding Sets Sail”, The National Interest, February 8, 2017, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/chinas-naval-shipbuilding-sets-sail-19371

“Xi to head central commission for integrated military, civilian development”, Xinhua News Agency, January 22, 2017, http://www.xinhuanet.com//english/2017-01/22/c_136004750.htm

Alex Wooley, “Float, Move, and Fight: How the US Navy Lost the Shipbuilding Race”, Foreign Policy, October 20, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/10/10/us-navy-shipbuilding-sea-power-failure-decline-competition-china/

Thomas Shughart, “Mind the Gap: How China’s civilian shipping could enable a Taiwan invasion”, War on The Rocks, August 16, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/08/mind-the-gap-how-chinas-civilian-shipping-could-enable-a-taiwan-invasion/

For an insightful look at how far the PLA Ground Force is pushing its vision of combined arms warfare down to the level of individual battalions, see Joshua Arostegui (Fall 2020). “An Introduction to China’s High-Mobility Combined Arms Battalion Concept”, Infantry, pp.12-17, https://www.benning.army.mil/infantry/magazine/issues/2020/Fall/pdf/5_Arostegui-HIMOB.pdf

Michael Kofman, “Russian Performance in Russo-Georgian War Revisited”, War on The Rocks, September 4, 2018, https://warontherocks.com/2018/09/russian-performance-in-the-russo-georgian-war-revisited/

Mandip Singh, “Learning from Russia: How China used Russian models and experiences to modernize the PLA”, Mercator Institute for China Studies, September 23, 2020, https://merics.org/en/report/learning-russia-how-china-used-russian-models-and-experiences-modernize-pla

Jack Watling, “The Future of Fires: Maximising the UK’s Tactical and Operational Firepower”, RUSI Occasional Papers, 27 November, 2019, https://static.rusi.org/op_201911_future_of_fires_watling_web_0.pdf

Lester Grau & Charles Bartles, “The Russian Reconnaissance Fire Complex Comes of Age”, Changing Character of War Centre, Oxford, May 1, 2018, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/55faab67e4b0914105347194/t/5b17fd67562fa70b3ae0dd24/1528298869210/The+Russian+Reconnaissance+Fire+Complex+Comes+of+Age.pdf; Scott Crino & Andy Dreby, “Turkey’s Drone War in Syria: A Red Team View”, Small Wars Journal, April 16, 2020, https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/turkeys-drone-war-syria-red-team-view

Marcus Clay & Dennis J. Blasko, “People Win Wars: The PLA Enlisted Force, and Other Related Matters”, War On The Rocks, July 31, 2020, https://warontherocks.com/2020/07/people-win-wars-the-pla-enlisted-force-and-other-related-matters/

Dennis J. Blasko, “10 Reasons why China will have trouble fighting a Modern War”, War on the Rocks, February 18, 2015, https://warontherocks.com/2015/02/ten-reasons-why-china-will-have-trouble-fighting-a-modern-war/?singlepage=1

Dennis J. Blasko, “PLA Weaknesses and Xi’s Concerns about PLA Capabilities”, Testimony given to the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, February 7, 2019, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Blasko_USCC%20Testimony_FINAL.pdf

Fumio Ota, “Sun Tzu in Contemporary Chinese Strategy,”, Joint Force Quarterly, No. 73, April 1, 2014. National Defense University Press, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Publications/Article/577507/sun-tzu-in-contemporary-chinese-strategy/

A sketch of this kind of “phased invasion” is outlined in Piers M. Wood & Charles D. Ferguson (2001). “How China Might Invade Taiwan”, Naval College War Review Vol 54 (4),https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2535&context=nwc-review

A blockade and other plausible scenarios are discussed in David Lague & Maryanne Murray, “T-Day: The Battle for Taiwan”, Reuters Investigates, November 5, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/taiwan-china-wargames/

Tanner Greer, “Taiwan Can Win a War with China”, Foreign Policy, September 25, 2018, https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/09/25/taiwan-can-win-a-war-with-china/

Tanner Greer, “Why I Fear for Taiwan”, Scholars Stage, 11 September, 2020, https://scholars-stage.org/why-i-fear-for-taiwan/